William Blake has never been exactly my cup of tea. When it comes to English Romantic poets, I’m more of a Byron and Wordsworth guy, and I like cats too much to get much pleasure out of thinking about Blake’s tiger “burning bright, / In the forests of the night.” But epidemiologist Amitha Kalaichandran had a riveting op ed piece about the COVID-19 pandemic today in the New York Times’ opinion section.

The headline did something the Times’ headlines rarely do — it grabbed my attention: “How Can We Bear This Much Loss?”

And the subhead let me know I wouldn’t be wasting my time by reading the piece: “In William Blake’s engravings for the Book of Job [Kalaichandran] found a powerful lesson about grief and attachment.”

Kalaichandran has her MD from the University of Toronto and a master’s in global disease epidemiology and control from Johns Hopkins. A 200-hour registered yoga teacher and mindfulness facilitator, she explained on Twitter this morning the subject of grief “has been on my mind for months: navigating our attachments during this challenging time,” and her op ed piece is based on a talk she gave to the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation.

Grief has been on my mind, too, in this time of pandemic. I’ve blogged about it HERE and HERE. And, as Kalaichandran acknowledges right off the bat, we’re not done with grieving:

As we pass the grim milestone of 200,000 deaths from Covid-19 — only the 1918 flu pandemic and World War II took more American lives — we know that the grieving has only just begun. It will continue with loss of jobs and social structures; routines and ways of life that have been interrupted may never return. For many, the loss may seem too swift, too great and too much to bear, each story to some degree a modern version of the biblical trials of Job.

So when Kalaichandran was asked to speak to the hospice group, she says, the story of Job resonated with her because it raises the same questions the pandemic does:

… How would I counsel others to cope with losses so terrifying and unfair? How could those grieving find a sense of hope or meaning on the other side of that loss?

In my research I found myself drawn to the powerful rendition of the Book of Job by the 18th-century British poet, artist and mystic William Blake, in particular his collection of 22 engravings, completed in 1823, that include beautiful calligraphy of biblical verses.

Blake?

Why Blake? I hadn’t read anything of Blake’s in 50 years. But I was drawn in by Kalaichandran’s headline (or, no doubt more accurately, the Times’ copy desk’s), so I refreshed my memory.

According to Wikipedia (my go-to source for all human knowledge), Blake “was considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views.” Welp, I certainly concurred with his contemporaries. I had to read a couple of his poems in grad school, and I’m sure we plodded through “The Tyger” when I was teaching English 113 (“Intro to Lit”) at UT-Knoxville. Burning bright or otherwise, it was in all the anthologies.

Wikipedia adds, however, that Blake “is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work.”

On reconsideration, I guess I have to concur with that, too.

At any rate, Kalaichandran finds some powerful lessons in the story of Job, more precisely in William Blake’s collection of 21 Illustrations of the Book of Job:

Job is conflicted — at times he still has his faith and trusts in God’s wisdom, and other times he questions whether God is corrupt. Finally, he demands an explanation. God then allows Job to accompany him on a tour of the vast universe where it becomes clear that the universe in which he exists is more complex that the human mind could ever comprehend.

Though Job still doesn’t have an explanation for his suffering, he has gained some peace; he’s humbled. Then God returns all that Job has lost. So, the story is, in large part, about the power of one man’s faith. But that’s not all.

Frankly, William Blake’s engravings still don’t do a whole lot for me.

But the story fits.

And Blake’s retelling of it in the engravings is nothing if not hopeful. His faith was certainly idiosyncratic (which means I shouldn’t sit in my glass house and throw stones at him), but powerful. As it is written in the book of Wikipedia:

[Blake] did not hold with the doctrine of God as Lord, an entity separate from and superior to mankind; this is shown clearly in his words about Jesus Christ: “He is the only God … and so am I, and so are you.” A telling phrase in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is “men forgot that All deities reside in the human breast”.

Kalaichandran finds hope in Blake’s engravings, which faithfully chronicle the story of Job, who loses “seven sons and three daughters … seven thousand sheep, three thousand camels, five hundred yoke of oxen, five hundred donkeys, and very many servants” (Job 1:2-3 NRSV). In the end of the story he gets them back, with interest. More importantly, he gets understanding.

She also finds hope in the Buddhist principle of non-attachment:

So, the Book of Job isn’t just about grief or just about faith. It’s also about our attachments — to our identities, our faith, the possessions and people we have in our lives. Grief is a symptom of letting go when we don’t want to. Understanding that attachment is the root of suffering — an idea also central to Buddhism — can give us a glimpse of what many of us might be feeling during this time.

We can recall the early days of the pandemic with precision; rites that weave the tapestry of life — jobs, celebrations, trips — now canceled. In our minds we see loved ones who will never return. Even our mourning is subject to this same grief, as funerals are much different now.

How much we’ve lost! How much more will we lose before we have responsible adults in government again and the pandemic is brought under control? I’m tempted to go off on a long-winded tangent here about detachment. But I won’t. (Something about glass houses, remember?) I’ll just try to cultivate the Zen attitude Kalaichandran recommends.

“Zen is a way of being,” says commenter “justanotherperson” in the crowdsourced Urban Dictionary website. “It also is a state of mind.”

See? I don’t get everything I know from Wikipedia. I also find Urban Dictionary to be a fount of wisdom. In fact sometimes I prefer it to more staid, traditional sources.

“Zen involves dropping illusion and seeing things without distortion created by your own thoughts,” adds “justanotherperson” on Urban Dictionary.

And one of my all-time favorite definitions was submitted by “Mr. Shades”:

[Zen] n: a state of coolness only attained through a totally laid-back type of attitude.

adj.: used to describe someone/something that has reached an uber state of coolness and inner peace.

That’s not exactly how Robert Aitken or Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki would put it, but it works for me.

So when Amitha Kalaichandran conjures up the Book of Job to help members of the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation deal with a global pandemic, I think she’s invoking something powerful, timely and, I believe, universal. She says:

As difficult as it is now, in the midst of a pandemic, it is possible — in fact, probable — that after this cycle of pain we feel as individuals and collectively that we might emerge with a greater understanding of ourselves, faith (if you’re a person of faith), and our purpose.

The word “healing” is derived from the word “whole.” Healing then is a return to “wholeness” — not a return to “sameness.” Those who work in hospice know this well — the dying can be healed in the act of dying. But we don’t typically equate healing with death.

Ultimately, to me, that’s the lesson offered by Blake’s Job: understanding his role in a wider universe and cosmos, transformed in his surrender, and the release from the attachments to his old life. Job had the benefit of journeying across the universe to understand his life in a larger context.

We don’t. But we do have the benefit of being his apprentices as we begin to emerge from this period, and begin to choose whether it propels us forward or keeps us stuck in pain, and in the past.

And that’s where Kalaichandran opens my eyes, at least a little, to William Blake’s artistry. Toward the end of her op ed piece, she talks about the engravings:

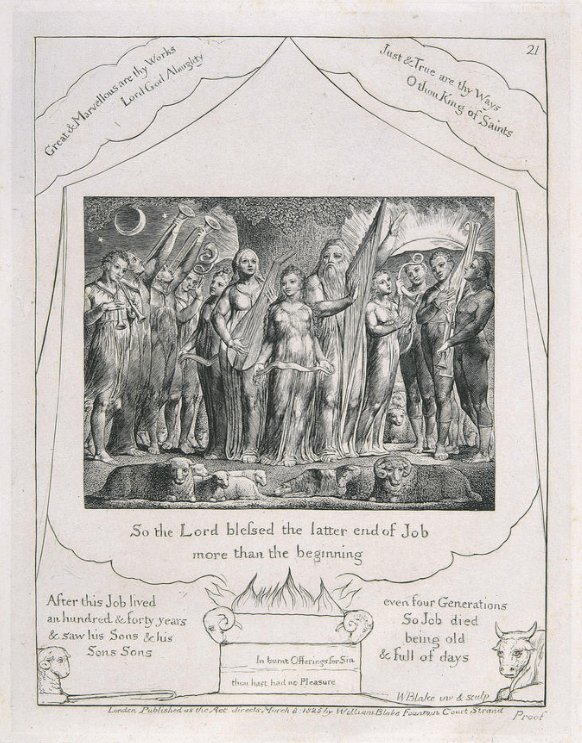

In Blake’s penultimate illustration in this series Job is pictured with his daughters. Notably Blake doesn’t write out this verse from Job; instead he writes something from Psalm 139: “How precious also are thy thoughts unto me, O God! How great is the sum of them!” In the very last image, however, God has returned all he had taken from Job — children, animals, home, health and more. Here, Blake encapsulates Job 42:12: “So the Lord blessed the latter end of Job more than his beginning: for he had 14,000 sheep, and 6,000 camels, and 1,000 yoke of oxen, and 1,000 donkeys.”

Blake intentionally didn’t make the last image a carbon copy of the first, likely in order to reflect new wisdom: an understanding that we are more than just our attachments. The sun is rising, trumpets are playing, all signifying redemption. Job became a fundamentally changed man after being tested to his core. He has accepted that life is unpredictable and loss is inevitable. Everything is temporary and the only constant, paradoxically, is this state of change.

“So,” Kalaichandran asks, “where does all of this leave us now?”

I can’t help thinking of all those camels and donkeys, let alone Job’s children. Blake tells us in the engraving (copied above from — where else? — Wikipedia), “After this Job lived an hundred & saw his Sons & his Sons Sons, he says, paraphrasing the King James bible, “even four Generations[.] So Job died being old & full of days.”

And where does this leave us?

I very much doubt we’ll get back our camels and donkeys — or their 21st-century equivalents. (Although I do hope we can install a new battery and get my car started again after we get a safe, reliable vaccine.) But Kalaichandran’s op ed piece was a reminder we can at least strive for detachment and peace of mind. Even though the universe is still more complex that the human mind could ever comprehend.

Citation. Amitha Kalaichandran, “How Can We Bear This Much Loss?” New York Times, Sept. 23, 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/23/opinion/grief-covid-book-of-job.html.

Nice!

LikeLike