Even before Pennsylvania was called for Trump, I shut off the internet Tuesday night and went to bed with a good book. The news was too much to bear. By coincidence, Thomas Cahill’s How the Irish Saved Civilization had come in the mail that afternoon. So I picked it up and read, in the very beginning of the first chapter:

On the last cold day of December in the dying year we count as 406, the river Rhine froze solid, providing the natural bridge that hundreds of thousands of hungry men, women, and children had been waiting for. They were the barbari — to the Romans an undistinguished, matted mass of Others, not terrifying, just troublemakers, annoyances, things one would rather not have to deal with — non-Romans. (11)

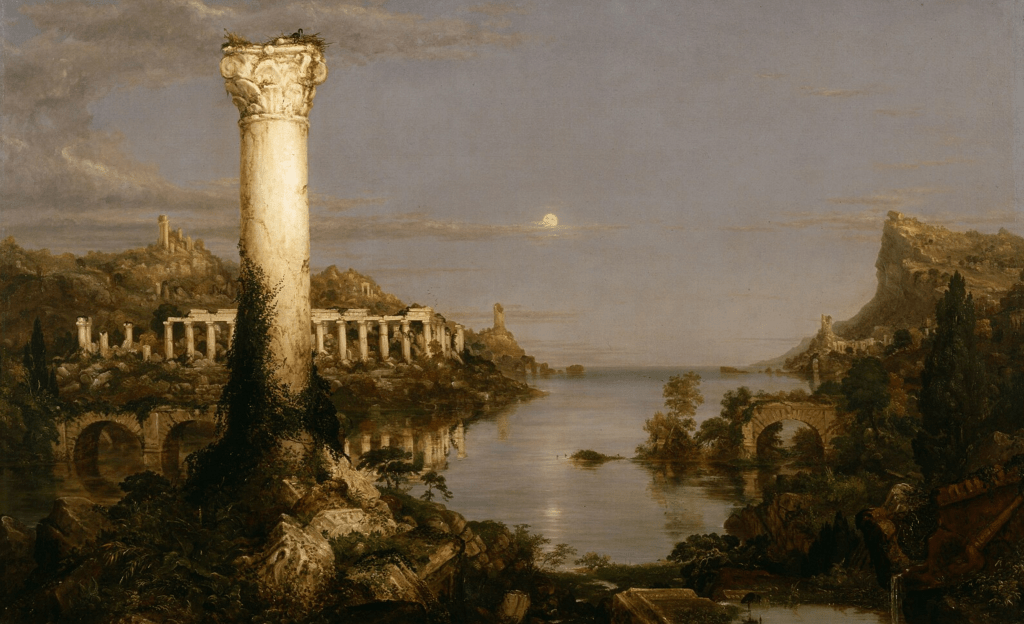

My ancestors! Cahill wasn’t exactly giving me the escapism and comfort I’d been looking for. Only four years after the Germanic tribes crossed the Rhine, a tribe known as the Visigoths sacked Rome; and 70 years later, the Roman Empire ceased to exist. Cahill’s book has a happy ending, if you can say that about history. His thesis that after the fall of Rome in 476, Irish monks painstakingly copied some of the classics of Greek and Roman antiquity and in doing so, prepared the way for a rebirth of Western civilization. But this image of ragged Germanic tribes at the gates of a dying empire didn’t go away.

In fact, it called to mind another article I’ve been reading lately. In the current issue of Commonweal (Dorothy Day’s old magazine), a 2011 article by financial writer Charles R. Morris was reprinted. Writing in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crash, Morris said, bluntly, “The rich have recovered — the country hasn’t.” Commonweal’s editors summed it up for him in a billboard or pull quote:

Is the United States really turning into a creaky, debt-ridden, class-based, post-imperial society? The sad and bitter answer may well be yes.

In a headnote to last month’s reprint, the magazine’s current editors repeated the imgage — “absent an FDR-like push for a stricter and more progressive tax regime and tougher regulations against financial chicanery, America was destined to become a ‘debt-ridden, class-based, post-imperial society’.” (The article is available online, by the way. Click HERE.) The same conditions, they added, still exist today.

And Cahill’s image of “weary, disciplined soldiers” of a dying empire looking down on “anxious, helter-skelter tribes” — my ancestors — has a resonance I can’t shake off. With today’s election I’m convinced our empire, such as it is, will go the way of the Romans.

It’s clear enough the Obama, Biden and first Trump administrations — Democrats and Republicans alike — did little or nothing to address the economic inequities that brought on the 2008 crash, and I plan to study Morris’ article in some detail. Are we creating a permanent, debt-ridden underclass? How much did income inequality have to do with Trump’s victories? (Richard V. Reeves of the Brookings Institute had a thought-provoking article in 2016, headlined “Inequality built the Trump coalition, even if he won’t solve it.”) Was Bernie Sanders right all along?

And it raises questions in my own mind. What do Trump’s base, the millions of Americans who felt left out of the Biden administration’s economic recovery plan, have in common with those Germanic “others” who crossed the Rhine into a dying Roman Empire in 406 CE? “To themselves they were, presumably, something more [than that],” Cahill reminds us. Yes! And yes again! I may be a lateral descendent, in fact, of the northern European Saxons who crossed the river near Mainz, according to St. Jerome; I would like to think they were more than “things [the Romans] would rather not have to deal with,” as Cahill so eloquently puts it.

Jesuit spirituality comes to the rescue

In the meantime, Tuesday’s election was a hard punch in the gut. I knew the electoral college could go either way, but I never expected the popular vote to go for a neofascist self-proclaimed wannabe dictator. I thought Kamala Harris’ campaign was inspiring, and I’m going to have to take some time to grieve the loss of optimism, yes, of joy, and the loss of my sense of what America might be. Should be. Let’s call it what it is.

I must not be the only one feeling that way. Today’s lead story on the Jesuit magazine America’s website is headlined “The day after Trump’s victory: searching for mercy, justice and God’s providence.” In it Sam Sawyer, the magazine’s editor-in-chief, warns, among other things:

Work for justice will certainly be necessary. Mr. Trump campaigned on the promise of mass deportations, which would tear families apart and destabilize communities across the country. His running mate, JD Vance, estimated that they could aim to remove as many as one million people per year. It is impossible to imagine such a policy being carried out justly or effectively, except insofar as the effect being sought is deeper fear among immigrants and deeper division in our nation. […] Our immigrant brothers and sisters will need voices raised up in their defense, and the Catholic Church especially must be a champion of solidarity with them.

Also prominently displayed this morning was a reprint of a how-to story by James Martin, author of popular books on Jesuit spirituality, prayer and his reflections on a tour of the Holy Land. First published just before the 2020 election, it’s titled “Jesuit tools to help you survive the election (and its aftermath).” and it came in handy during the violent aftermath of that election. This year’s hasn’t been violent so far (something Sawyer gave thanks for), but it’s still handy for those of us who have to work through our grief. Martin lists three tools:

- Discernment of Spirits. A way of making decisions by “paying attention to our interior life.” If something feels right, gives us a feeling of peace, it’s probably a good idea; if it agitates us, it isn’t. “In short, hope comes from God,” Martin says. “Despair does not. So pay attention to those voices. Listen to the voice of hope, not despair.”

- Presupposition. “Essentially,” says Martin, “it means giving someone the benefit of the doubt. Give them, as an old Jesuit used to tell me, ‘the plus sign’. […] The ‘plus sign’ will help you weather the storm with more equanimity and with less danger of jumping down the other person’s throat.”

- Detachment, or ‘indifference.’ Says Martin, “Now, that does not mean, ‘I don’t care about anything’ or ‘Who cares?’ or ‘Whatever.’ […] You care about important issues and follow your conscience in responding to pressing social needs, but you are also able to step back in order to live more sanely and even be more productive in the long term.”

When Martin talks about detachment, I discern something that makes me feel like he’s talking directly to me:

What does this mean, practically speaking? Well, can you be free from the need to enter into every single political argument in your family? Moreover, can you be free of the need to win those arguments? Can you be free of the need to obsessively watch every news program about the election and its aftermath? Can you be free of the need to answer every barbed comment online?

But I especially like his explanation of “discernment of spirits,” the Jesuit decision-making guide. It was developed by St. Ignatius of Loyola, who founded the Jesuit order in the 1500s. Ignatius spoke of “good spirits” and “evil spirits,” or spirits of consolation and desolation, but they translate well in the secular world of the 21st century. Martin explains the discernment of spirits like this:

How does that help us in the 2020 post-election season? Ignatius said that for those of us on the right path, the spirit that moves us toward God will be experienced one way, while the spirit that moves us away from God will be experienced in another. Simply put, the “good spirit” will be one of calm, uplift and encouragement. The “bad spirit” will cause “gnawing anxiety” and throw up “false obstacles.”

In essence, the good spirit gives hope, the bad spirit despair.

So whenever you feel hopeless or despairing, you can be sure that is not coming from God.

How often have we felt that in the last few weeks and months? But it is a great help to know any time that you feel interiorly (or hear exteriorly) these voices—“It’s hopeless,” “Things will never get better” or “We’re doomed”—that it is not coming from God.

By contrast, any time you hear these voices—“You’ll get through this,” “Things are never lost” or “You have many resources to help you”—know that this is coming from God.

I don’t believe in whatever spirits were roaming around Europe in the 16th century, but I’ve found that Ignatian discernment, as it’s sometimes called, works in the 21st. It also chills me out when I need it. This I discovered last year when I was being wheeled into an operating room on a gurney and couldn’t think of anything else to say, so I tried a bit of deep breathing, saying “consolation” as I inhaled and “desolation” as I exhaled.

I’m sure St. Ignatius would be horrified by the way I’m oversimplifying his exercises, but it works. In fact, I’m going to try it tonight.

Links and Citations

Thomas Cahill, How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland’s Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe (New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 1996): 11, 14-18.

James Martin SJ, “Jesuit tools to help you survive the election (and its aftermath),” America, Nov. 2, 2020 https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2020/11/02/jesuit-spirituality-election-2020-james-martin.

Charles R. Morris, “The Two Economies,” Commonweal, Feb. 28, 2011

https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/two-economies.

Richard V. Reeves, “Inequality built the Trump coalition, even if he won’t solve it,” Brookings, Sept. 26, 2016 https://www.brookings.edu/articles/inequality-built-the-trump-coalition-even-if-he-wont-solve-it/.

Sam Sawyer SJ, “The day after Trump’s victory: searching for mercy, justice and God’s providence,” America, Nov. 6, 2024 https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society/2024/11/06/trump-election-win-mercy-justice-catholic-249213.

[Uplinked Nov. 6, 2024]

This has got to be one of your best. ❤

LikeLike