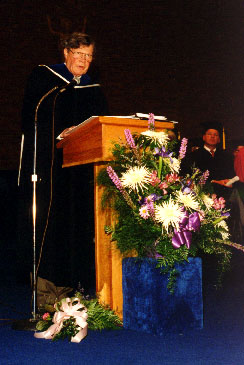

John Knoepfle, who died Saturday at the age of 96, was awarded an honorary doctorate in 1999 by Springfield College in Illinois (later Benedictine University Springfield). As the faculty adviser/de facto editor of the campus literary magazine at the time, I obtained John’s permission to publish his commencement address to the class of 1999, perhaps best described as a set of brief meditations on poems he was working on at the time — many of them about the peace process then beginning in the north of Ireland — and a wish, or perhaps a prayer, that “you, the class of 1999, are graduating into a new century. And it may be in some small way each one of you can mitigate the terrible things that happened in this (20th) century.”

More recently, John and I played together in jam sessions at Hickory Glen Apartments in Springfield, and I can attest he played a righteous, soulful harmonica.

But he is best known as a poet and author of literary works ranging from translations (with Wang Shouyi) of ancient Chinese poetry to the Dim Tales, a collection of downstate Illinois aphorisms of his own invention that somehow manage to be earthy, sophisticated, witty, subtle, rambunctious and/or deeply moving all at the same time.

John’s speech appears below as he delivered it in May 1999. (I was lucky enough to find an HTML copy today on an old hard drive, and it is formatted exactly as it was on the software available to me at the time!) John was a master of understatement, and he wasn’t one to claim any dramatic or towering insights. But a couple of things stand out 20 years later.

One is his prayer for the Class of 1999 as it faced into a new century:

pray for everyone so that we can redeem all the bleak, bright hours when we did not pray for ourselves

Call it a prayer for the peacemakers, and I think we’re pretty close to the mark. The other is something that John and his wife Peg had made into greeting cards and suggested posting on the refrigerator door, because it was like a little recipe for peacemaking in relationships. Debi and I kept one, yes, on our refrigerator door:

love is like a bowl

so when you break it

glue it together

if it won't hold water

fill it with apples

Good advice 20 years ago. Still good advice.

— Peter Ellertsen (“Hogfiddle“), admin, Ordinary Time

A Set of Poems with Commentary

for the 1999 graduates of Springfield College in Illinois

by John Knoepfle

Editor’s note: John Knoepfle of Auburn, poet and retired Sangamon State University creative writing professor, received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree this year from SCI and, as is customary, delivered the commencement address. He has written more than 20 books of poetry, including Poems from the Sangamon (1985) and the chinkapin oak (1995), and has a longstanding interest in the Native American peoples who once lived in what is now Illinois. Commencement exercises were May 19, during Memorial Day weekend. Knoepfle’s address follows.

Salutations. To make this address I am going to take my privilege as writer and present to you a set of poems with commentary dedicated to the Springfield College in Illinois class of 1999.

I

At Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington they have a prayer room on the floor above the entrance to the Student Union, a small place with a bench or two to meditate or pray. There’s an open Bible just under a brilliant stained glass window and spiral notebooks where students can write their thoughts. It makes a man feel old just reading them. The students are so young.

But the reason the prayer room is there in the Student Union is because during World War II a graduate of Illinois Wesleyan had become a navy chaplain, and he was on a troop transport in the North Atlantic that was torpedoed. The poem tells the story.

prayer room poem

commemorated here those who died in the torpedoing of the uss dorchester february 3 1943 george fox john washington alexander goode charles poling died praying together refusing the overcrowded lifeboats their jackets given to others four chaplains a minister a minister a rabbi a priest so remarkable a text all that they could be they were

The poem is about four men who shared something — and shared everything. They were people that we mourned for with admiration. In their dying they became larger than life. In the midst of the most destructive war in history they bound themselves together in charity and concord.

II

This poem about a sign honors another man of peace — my brother-in-law Matt Sugarman, who died Sunday three weeks ago after a long illness. Born in Brooklyn with a background in business administration and experience in managing an elevator factory, Matt seemed an unlikely candidate for the post of California park ranger. But by following his heart and having serendipitous good luck, that’s what he became — to the benefit of all us.

Matt was chief ranger at Marshall Gold Discovery State Park in California – Sutter’s Mill, the place where the gold rush began. He called it “the most important historical site west of the Mississippi.” But he would not call the l50th year anniversary of the Gold Rush a celebration. It should be commemorated, he said, not celebrated. Too many terrible things happened during the Gold Rush — the persecution of Chinese immigrants, the ethnic cleansing of native Americans and the destruction of the natural environment itself. Matt believed that these hard truths should faced with honesty. “The point is,” he said once, “we as a society have to recognize our participation in what was a genocide.”

In an extraordinary article he wrote about facing death, he said in conclusion: “I am a Jew. Next year I’ll be in Jerusalem.” In this poem, the “city on the hill” is Jerusalem.

Matt this is your sign left hand palm forward over the heart a high plains sign a sign for no ill intentions a sign for coming in peace a sign for the open heart brother to brother a sign for you Matt brother to brother the city is on the hill look up Matt the sign the sign is everywhere

III

I traveled to Ireland in 1996 and 1998. County Claire, mentioned in this poem, is in the West of Ireland, and the Cliffs of Moher are 800-foot drops at the edge of the Atlantic — the furthest western land mass this side of the coast of North America. I assume the song I am describing here grew from the memory of the famine that struck Ireland in the summer of 1847 and took a million people with hunger and attendant diseases. I visited Skibbereen in the south of County Cork and saw the famine pit in the cemetery there — a grassy field that my sons could have played soccer on. There were 10,000 buried there and I assume some of them were four generations ago uncles and aunts and cousins of mine.

the claire festival of traditional singing

their songs had melodies not to be written down too lost in between notes like the winds of moher each singer turned from the mike searching the key then turned back and each became only a voice the men hands held stiff in their pockets the women arms at their sides and then she went up on stage and told us her song came from a woman grieving her twelfth child lost and we heard a voice taking a voice ancient as the language itself the dead silence of the room it was in that still time we saw famine enter the room and we watched his hair turn gray

It seems to me that what is human in us can outlast famine and Holocaust even as we are coming this day to the end of a century which was the most brutal in the history of the world — the wars alone have taken the lives of 148 million people. And it occurs to me that you, the class of 1999, are graduating into a new century. And it may be in some small way each one of you can mitigate the terrible things that happened in this century — transform them in some way as the singer does in this poem.

Famine is male here because the powers that bungled the care for the Irish were masculine. I should add that the government of Holland was also dominated by men at the time, and the potato failed there as well as in Ireland But no one starved to death in Holland because the governors were men of understanding and compassion They listened to their intellect or as St. John Fisher has the phrase “to our Lady Reason.”

IV

Belfast has been the capital of Northern Ireland since 1921 and a place of strife and bloodshed between Protestant Loyalists and Catholic Nationalists for 400 years. Falls Road is a working-class [Irish] Nationalist neighborhood, plagued by generations of unemployment and a flash point for violence because it is near working-class [British] Loyalist neighborhoods. Elizabeth Groves who runs a community center at Falls Road, and May Blood, a labor union leader from a Loyalist background, dared to imagine and work for peace in their beleaguered city. They crossed the divide between their two neighborhoods and risked violent retribution in order to talk to each other and assert their common humanity. Women played a major role in the Good Friday Peace Accords. Without their leadership the accords probably would not have been signed. Today these women continue to work for peace, which they say must include both economic justice and civil rights.

This poem is based on Elizabeth Groves’ account of a meeting in Belfast where she sat across the table from a man who had killed friends of hers. She told him that she was afraid of him. That was how she was able to begin. In this poem I make childbirth a metaphor for peacemaking And I also try to show the leap of imagination and courage it takes to come to terms with your own history and that of your enemy.

Interestingly enough, when the members of the Falls Road Community Center were trying to decide if they should take part in the peace process, they were visited by a delegation from South Africa. The South Africans, who had spent years fighting apartheid and suffering from its violence, urged the community center to accept the risks involved in peacemaking and take part in the negotiations.

belfast on the falls road

and where is the incentive now in this time of amnesty forgiving time to forgive pinned to a conference painful as childbirth from a scarred womb or hands that should have been peaceful nailed here to this oak table and that man opposite and that man smiling now you knew him of old from the very edge of your life this one who killed your friends how could anyone endure the concord of his handshake sitting here in fear hands white-knuckled under the table saying I am afraid afraid of the teeth in your mouth bringing your dowry of shame from such a depth of reproach seeking a calm place estuary of what can be possible

V

A day later people from an Ulster television station came to interview members of our tour group. And we all did the best we could I was the last to speak, and the moderator wanted to know if I had roots in Ireland And I said, “Yes, I think they are in the famine pit in Skibbereen.” Then I thought awhile and said “I think that famines are political and that here in Northern Ireland there has been a famine of the soul for hundreds of years.” Then I was able to give them this prayer against famine which may have been broadcast in Ulster later.

prayer against famine

maker of the wheel that turns the stars place the shadow of your shadow between us and everything evil have mercy on the dead and on the living and on those who will be born in your good time protect us when we are tempted when we want to make ourselves the center of your world when we would deny others a place in the circle of your love cleanse our eyes oh god and pour your light into them so that we may see your creation in everyone on this earth

It’s difficult to write prayers because the temptation is to write in a kind of strange language that I call “church English.” I might note that the Kaddish prayers for Matt Sugarman are in a language so forthright and handsome that it makes you feel unworthy to even say them.

VI

This poem is called “Prayer at Commencement,” your commencement. I think I should preface it with a statement by Thomas Merton quoted by Jane Redmont in her book When in Doubt Sing: Prayer in Daily Life.

“Don’t set limits to the mercy of God. Don’t believe that because you are not pleasing to yourself, you are not pleasing to God. God doesn’t ask for results. God asks for love.”

prayer at commencement

pray for everyone so that we can redeem all the bleak, bright hours when we did not pray for ourselves

Remember that “commencement” means “to begin” or “to begin again.”

VII

This last poem is called “poem for everyone.” It is turning up in all kinds of improbable places on office walls and refrigerator doors, and I know for a fact that it has saved a marriage or two.

poem for everyone

love is like a bowl so when you break it glue it together if it won't hold water fill it with apples

And on this note, Class of 1999, I wish you well as you commence the rest of your lives. May you be bound together in charity and concord And in the words of the Peoria and Miami and Tamaroa people, who hunted in this valley: “May you be happy in a happy place.”

The Sleepy Weasel, Vol. 5, 1999-2000

What an amazing commencement address and how refreshingly more nuanced than most of them.(I taught at a college for 25 years and heard 25 of them.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes — I’m sure this was the only commencement address I ever listened to!

John’s poetry was nuanced, too. I guess he was best considered a regional poet, but early in his career he was associated with Robert Bly and James Wright, and yesterday I found a blurb by Kathleen Norris on his website at http://www.johnknoepfle.com/. Debi and I took John’s creative writing classes at Sangamon State (now UI-Springfield), and he was a kind, generous and unfailingly encouraging mentor to us both. He was like that with everyone in our little part of the world. Also a lifelong Catholic who made the decision to stay with the Church in spite of its manifold flaws; when I was struggling with my own decision whether to rejoin the church (lower case “c”) John’s example was important to me.

I’ll link to a longer, and more characteristic poem, on the Bradley University (of Peoria) website. https://www.bradley.edu/sites/poet/steel/poems/knoepfle.dot

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing John with us in a way we can so easily recognize him.

LikeLiked by 2 people