Swedes in Roger Williams’ Garden: Acculturation in Immigrant Churches, 1848-1860: Presentation for Conference on Illinois History, Abraham Lincoln Public Library and Museum Springfield, October 5-9, 2020.

When he filled out a quarterly report to the American Home Missionary Society on April 1, 1850, the Rev. Paul Andersen of the newly organized Scandinavian Evangelical Lutheran Church of Chicago reported a problem he wouldn’t have faced back in the old country. “An intelligent and in many respects a highly respected gentleman sent me word that he with his family wished to unite with our church,” he began. But the man “frequently worked in his shop on the Sabbath,” and Andersen’s congregation required “that only those who give credible evidence of a radical change of heart and who are living according to the precepts of the Gospel shall be admitted as members of the Church.” Andersen had come to America as a youth and studied at Beloit College on the frontier in Wisconsin, where he came to believe in an essentially Congregationalist view of the church as a gathered community of professed believers. But this put him at odds with some of his Norwegian parishioners, who had grown up with quite a different view of membership in the established state church. Complicating the issue was the fact that the AHMS made it a condition of its funding that new church members be required to document a conversion experience.

So Andersen told the man he couldn’t allow him to join the church, even though he “respected him as a friend and a neighbor.” That came as a shock to the shopkeeper. “Ministers at home never said anything about it nor did they refuse to admit us to communion,” he protested. To this Andersen replied he was “only endeavoring to correct abuses in so far as we deviated [in America] from the State Church.”1 History doesn’t record how – or whether – they resolved the issue, but Andersen was not the only Lutheran pastor who faced it.

Especially in a day of revivals and camp meetings, most Protestant Americans were expected to have a conversion experience – to be “saved” or “born again” – before they were admitted to church membership. But in the old country, Swedes and Norwegians by law were baptized as infants into the Lutheran established church; they were catechized and confirmed as youngsters, and no further action was necessary for them to qualify for church membership – or to receive communion.2 “The Swedes have been members of a State Church,” explained the Rev. Lars Paul Esbjörn, a Swedish colleague of Andersen’s who also received funding from the AHMS, “and the greater number of them have lived in places where the true religion, conversion, and new birth and sanctification are unknown or mentioned with contempt and disdain.” Writing on Feb. 28, 1850, Esbjörn said “[t]he Swedes consider it an infamy for any one at all to be denied the Lord’s Supper” and he feared he would lose members if he enforced the rule.3 The cultural norms were quite different, and acculturation would be difficult.

At the bottom of Andersen’s and Esbjörn’s dilemma was a theological and cultural difference between most 19th-century American Protestants and immigrants from Lutheran countries like Norway and Sweden. While Swedish and Norwegian Lutherans had their own differences, both theological and cultural, in the early days they joined forces. Rather quickly they would fashion a compromise with the Americans, a process by which prospective members of their congregations would pledge to seek a conversion experience and abide by standards committing them to a “new life” in the church.

This compromise would be cobbled together out of American, northern European and confessional Lutheran practices by a complex process of acculturation, or cultural blending, that anthropologists sometimes call creolization.4 The terms are clunky, but they have the advantage of reflecting the complexity of the process better than earlier studies of “Americanization” that tended to assume that immigrants simply shed their Old World cultures and became Americans, when in fact the interaction between immigrant and native cultures was, and is, a complex multidirectional process. Indeed, some of it had already taken place in the old country. Many Swedish immigrants were influenced by pietism, a European movement originating in 17th-century Germany that combined elements of Lutheran theology with a Calvinist, or Reformed, emphasis on personal piety and upright living. It was influenced by later English evangelists, and by the mid-1800s, Swedish pietists already had much in common with the Anglo- American evangelical movement. As historian James A. Bratt once put it in an address to a Swedish- American heritage group, “Acculturation is a two-way, not a one-way, street,” and the experience of Swedish Lutheran pastors typified the process.5

In recent years, cultural anthropologists have used metaphors of hybridity, bricolage and creolization for the phenomenon. Especially influential has been Ulf Hannerz of the University of Stockholm, who borrowed the term creolization from linguists – to whom it signifies a colonial language with mixed new- and old-world antecedents, usually reflecting different racial and cultural backgrounds – and uses it to describe a generalized process whereby subordinate, or peripheral, cultures create hybrid forms that “put things together in new ways.” Like other students of the phenomenon, he quotes post-colonialist novelist Salman Rushdie, who once said his writing “rejoices in mongrelization and fears the absolutism of the Pure. Mélange, hotchpotch, a bit of this and a bit of that is how newness enters the world.” While creolization theory can be seen as a post-colonial reaction to what cultural anthropologist Jan Nederveen Pieterse perceives as a “McDonaldization” of global culture, the process has been going on at least since the ancient Greeks encountered the Egyptians and Persians and continues to the present.6

Hannerz’ metaphor has been used to describe hybrid cultural forms ranging from New Orleans jazz; the Haitian Kreyòl language; French colonial architecture in early Illinois; the blended ecclesiastical culture developed by Russian Orthodox Alaska Natives; and the “polkabilly” music of mixed German, Czech and Scandinavian dance bands. While the term originated with mixed-race cultures in Latin America and the Caribbean, folklorist James P. Leary says it applies just as well to northern European immigrants in the upper Midwest, whose “musical interactions have long been distinguished by egalitarianism, by freewheeling accommodation and blending across complex boundaries.” He adds. “Here reside North Coast creoles.”7 In that broader context, shorn of its post-colonial connotations, we can say without hesitation that Swedish- and Norwegian-American Lutherans of the mid-19th century put together a bit of this and a bit of that, thereby combining European state church with Anglo-American denominational and frontier revivalist practices in new ways to form voluntary religious associations without government assistance. The result was something that wasn’t quite like any of its antecedents.

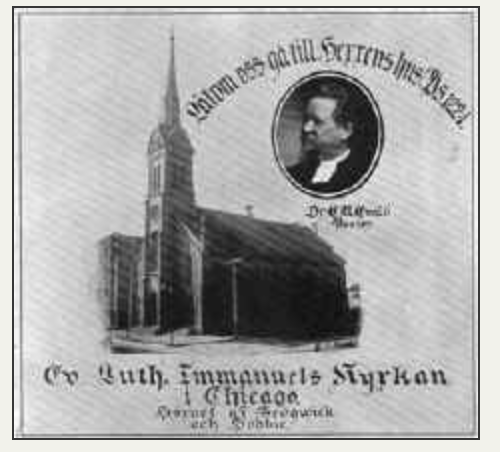

In the winter and spring of 1850, Esbjörn and Andersen would accept new members into their fledgling congregations who sincerely “promised to use the Word of God and to pray for their conversion, and on the basis of their having been members of the State church at home were not to be compared with those in this country who stand outside the church,” as Esbjörn reported to the Home Missionary Society in February. On March 18 he organized a congregation in Andover. Only 10 communicants met the eligibility requirement, but the area had “a significant number of Swedes from Östergötland and Småland” living there, and 70 who attended services in Andover. In the coming months, Esbjörn set about recreating something like a Swedish parish in western Illinois, a far-flung geographical unit with satellite congregations from Galesburg to Moline.8 At the same time Andersen’s growing congregation in Chicago, which took in both Swedes and Norwegians, would spin off both Swedish (Immanuel) and Norwegian (Lake View) congregations on the North Side. And as more Scandinavian Lutherans settled throughout the upper Midwest, Esbjörn’s congregation in Andover would become the mother church of the Augustana Lutheran Synod formed in 1860. At issue between the Lutherans and the Home Missionary Society was an evangelical doctrine of the Second Great Awakening, ultimately derived from the Calvinism of Puritan New England, restricting membership in a covenanted church to an elect who could prove they were chosen for salvation.

As historian Garry Wills suggests in Head and Heart: American Christianities, this covenant theology was intricately bound up with the American ideal of separation of church and state, or, in Roger Williams’ words, a “hedge or wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world.” Through American history these ideas have been inextricably bound together, and the separatist ideal of a pure community of believers set apart from the wickedness of the world was inherent in the 19th- century ideal of a system of voluntary religious associations, free of government interference in a New World. Diarmaid MacCulloch, the English historian, Diarmaid MacCulloch, the English historian, catches its spirit very well, when he speaks of “the rhetoric of covenant, chosenness, of wilderness triumphantly converted to garden … served up with a powerful dose of extrovert revivalist fervour.” All of this, he says, in his magisterial survey Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years, would lead to “a Christianity shaped by a very different historical experience from western Europe.”9 Most Swedish immigrants did not see the world that way, and they quickly set about adapting their European pietist heritage to Protestant American expectations.

The Swedes were not alone in doing so. Speaking in 2012 to the Augustana Heritage Society, historian James Bratt of Calvin College suggested the experience of the Dutch Reformed churches he has studied matched that of the Swedes. It was not, he added, a simple matter of adjusting to freedom of religion in an American context. Nor was it a simple issue of personal piety and the “strict standards of a pure church,” even though European pietist impulses were part and parcel of the adjustment.10 “Rather,” he said, “a complex menu of combinations emerged, and in that matrix (cross-hatched, of course, by ethnicity) can be placed the full variety of denominations and affiliations that populated the German, Dutch, and Scandinavian church scene in the United States from the 1860s to the 1960s. The forge of this pattern, let us remember, was as much European as American.”

So the compromise membership policy that Esbjörn and Andersen worked out in the 1850s was one small part of a process of acculturation or creolization that in time would lead to a hybrid immigrant culture sometimes reified as Svensk-Amerika, or Swedish America. In time ethnic historians, especially Augustana Synod Lutherans, would collect documents and write books quoting copiously from Esbjörn, Andersen and their contemporaries, and the translations they lovingly compiled are a valuable – and accessible – source of information about how one group of immigrants adjusted the religious institutions they brought from the old world to the prevailing culture of 19th-century America.11 While their authors can be quite filiopietistic, they were thorough. And they document a process that I believe was repeated by other ethnic groups at other times and in other places. At the end of the day, the creolized institutions that Swedish- and Norwegian-American pastors like Esbjörn and Andersen, to slightly misquote Salman Rushdie, brought into the world a mélange, a hotchpotch, a bit of this and a bit of that. The church membership policy they worked out in the 1850s offers us a small window into their creolized world.

‘The garden … must of necessity be walled in’

In 1854 the Rev. Erland Carlsson of Chicago’s Immanuel Lutheran Church wrote a guidebook, Några råd och underrättelser för utwandrare till Amerikas förenta stater [some advice and information for emigrants to the United States of America]. He had been in Chicago for a year, arriving when Swedish members of Paul Andersen’s Norwegian church formed their own congregation and called him to be their pastor. Like other immigrant pastors, Carlsson often took in destitute countrymen, nursed cholera victims and served as an informal mentor to Swedish travelers. So he was full of useful advice for prospective immigrants back in Sweden. Chicago was an important transit point for Swedes bound for the upper Mississippi valley, and from them he gleaned recommendations ranging from travel arrangements to food on shipboard – offering suggestions on matters as mundane as currency exchange and shipboard provisions: “It would perhaps be well … to provide oneself with a few pounds of prunes, etc., for fruit soup, a few bouillon cubes (‘buillion de Poche’), together with a few bottles of good red wine and Maderia.”

Along more spiritual lines, he suggested reading material including “the Bible, Luther’s Postils [sermons], and some other good devotional book.” In this vein Carlsson continued:

To be sure, our countrymen, when they have come over here, will soon hear other advice concerning these devotional writings and Christian books than this which I have given; for, instead of being advised to procure such and to use them, they will be admonished, if not to burn them up entirely, then certainly to throw them away. “Away with Luther, away with the Catechism, away with every word of man!” so it goes. “We have the Bible, and that is enough.” … One will also often hear the same condemnation concerning our church’s customs and practices. In place of these, others are brought in, by which men are soon confused, with injury to their souls, inasmuch as upon these very things much greater weight is laid than our Lutheran Church ever placed upon the external form. But enough concerning this.

Interspersing his assessment of “the many intellectual winds which blow in the spiritual atmosphere of America” with practical advice on railroads, steamboats, innkeepers and various swindlers, Carlsson warned his countrymen, all of whom by law were members of the state Church of Sweden, not to:

… thoughtlessly or frivolously sell your birthright as a Lutheran, “pure Word and pure Sacraments,” for a mess of pottage, cooked together out of empty promises of some earthly benefits and a self-chosen spirituality spiced with bitter rantings about the church back home and a few Bible passages, twisted and torn from their context.12

If Carlsson felt embattled, he had ample reason. Swedish immigration was just beginning. Swedes in America had no institutional support from the church in the old country, and most American Lutherans were clustered in Pennsylvania and elsewhere along the East Coast. They were outnumbered everywhere, and they faced stiff competition from homegrown American denominations.

Reliable census data are hard to come by at the local level, but an estimated 214 Swedes lived in Chicago in 1850, their number growing to 1,070 in 1860. (During the same time, by way of comparison, the city’s population grew from 29,963 to 112,172.) In the 1850s, most Swedes lived side-by-side with a like number of Norwegians in “miserable shanties or … small and narrow rented rooms” on a marshy, windswept prairie along the north branch of the Chicago River. The North Side was mostly Irish and German, but Carlsson’s congregation competed primarily – and often bitterly – with a Swedish-language Episcopal church called St. Ansgar’s, named after a ninth-century archbishop who established churches in what are now Sweden, Denmark and Norway. Chicago was both a boomtown and a gateway to the Mississippi valley frontier, and an 1848 visitor from the South Carolina low country spoke of “emigrant parties” led by:

… wild, rough, almost savage looking men from North Germany, Denmark and Sweden – their faces covered with grizzly beards, and their teeth clenched upon a pipe stem. They were followed by stout, well-formed, able-bodied wives and healthy children. Neither cold nor storm stopped them in their journey to the promised land, on the frontiers of which they had now arrived. In most instances they followed friends who had prepared a resting place for them.13

Out in western Illinois, an important destination point for Swedish settlers, Esbjörn in the early 1850s tended little congregations in Andover, Moline and Galesburg, and an estimated 400 religious dissenters lived in a nearby utopian colony at Bishop Hill. Other Swedes were scattered in perhaps a half-dozen pioneer communities in northern Illinois, Iowa and the upper Mississippi valley.14 In these little outposts of Swedish culture they battled poverty, recurrent cholera epidemics and – at least in the opinion of the first Swedish pastors – Methodist and Baptist evangelists.

Swedish immigration was just beginning in the 1850s, and the U.S. Census of 1850 counted only 3,559 Swedish-born people nationwide. In the coming years, however, Swedish authorities estimated that as many as 3,000 a year would emigrate, mostly for America. In 1860, the U.S. Census counted 18,625 people of Swedish birth. No more than 20 percent of them affiliated with the Scandinavian-American Augustana Lutheran Synod formed that year, a percentage that would hold steady well into the 20th century. Others joined Methodist or Baptist churches that had active Swedish-language outreach programs, or local English-language Protestant congregations. And, according to Fredrika Bremer, a Swedish novelist and travel writer who visited America in 1850, still others “not infrequently come hither with the belief that the State Church and religion are one and the same thing, and when they have left behind them the former, they will have nothing to do with the latter.”15 That would hold steady, too.

In the mid-19th century, there just weren’t that many Lutherans in America to begin with. Historian Timothy L. Smith’s estimates are as good as any – he complied the available statistics for the year 1855 and reported a total of 205,049 Lutherans nationwide, compared to 1,577,014 Methodists and 1,105,546 Baptists. Moreover, the Lutherans were largely third- and fourth-generation German-Americans whose forebears had come to America long before, and they were influenced by what they called “new measures” of American camp meeting spirituality, including fire-and-brimstone sermons and the evangelical Protestant emphasis on being “saved” or converted.15 When Esbjörn set up shop in western Illinois, the wave of revivals and camp meetings known to historians as the Second Great Awakening was still in full swing, and he faced stiff competition from frontier evangelists. It was baked into the American system of voluntary religious associations, there as everywhere, and Esbjörn was especially troubled by Swedish-speaking Baptists and Methodists. One, by his account, preached:

… that the Lutheran church is dead; that it is the Babylonian harlot [and] … the Swedish preacher [Esbjörn] has come to burden these free citizens with the shackles and fetters of the State Church; that there are no Lutheran congregations in America: that the Methodists are the genuinely true Lutherans but with another name.16

And so on at great length. In Chicago, the Swedes’ most vigorous competition came from the Rev. Gustaf Unionus’ Swedish-language Episcopal parish. The Episcopal Church was considerably smaller than the Baptists and Methodists, with 105,350 members nationwide. Things got so contentious that at one point Unionus sued Esbjörn for libel, and Esbjörn was forced to issue an apology and retraction.17 It can be difficult for us today to separate out the facts from the attendant rhetorical flourishes, but it is clear that competition was unrestrained and often bitter.

The Swedes’ relationship with the Congregationalists and Presbyterians was more civil, but it too was complicated. Neither the Congregationalists (with 207,608 members nationwide) nor the Presbyterians (with 495,715 mostly split between “Old School” and “New School” factions) were as active in evangelizing the West as the homegrown Baptists and Methodists. But they had a presence at Knox College, an abolitionist institution founded in 1837 in Galesburg. And, more importantly for our purposes, through the American Home Missionary Society they helped finance the first Scandinavian Lutheran congregations in Illinois – in Chicago, Andover and Galesburg – until they could get on their feet financially. In some ways, this relationship was ahead of its time. In others, it wasn’t. Founded in 1826 by Congregationalists and New School Presbyterians, the AHMS routinely provided financial aid for what church historian Martin Marty of the University of Chicago terms “the more sedate and conservative eastern Protestant interests” on the western frontier – in essence what we now would call mainline Protestant churches – in competition with frontier Methodists and Baptists. Unusually ecumenical-minded for the 19th-century, the AHMS was willing to help Lutheran pastors, as long as they organized their congregations “on an evangelical foundation,” as a regional Home Mission Committee put it in December 1849.18 This committee recommended funding for Esbjörn’s parish in Andover, but AHMS assistance didn’t come without strings attached.

Both then and now, the term “evangelical” is fraught with difficulty because it had different connotations to Lutherans and other Protestant Americans. It derives from a Greek word for the gospels, and it was the term Martin Luther used for the church that grew up around his teaching; so in northern Europe it came to be applied to Protestants in general and Lutherans in particular. (When the Swedes and Norwegians created their own synod in 1860, they would call it an evangelisk-lutherska synod.) Yet for Americans, as church historians Robert Kolb and Carl R. Trueman point out, the term “has its roots in the revivals – and revivalism – of the eighteenth century.” In her historical survey The Evangelicals; The Struggle to Shape America, Frances FitzGerald usefully defines evangelicals, then and now, as stressing the bible “as the ultimate religious authority,” sin, atonement and – especially important for our purposes – “conversionism, or the emphasis on a ‘new birth’ as a life-changing experience.”19 Out of these disparate roots would grow trouble.

An important part of what the AHMS considered a proper “evangelical foundation,” according to Robert Baird, an influential Presbyterian who wrote a survey of American religion in1844, was an insistence that only parishioners who demonstrated an “outwardly moral life” could join the church and take the sacrament, or ordinance, of Holy Communion. “Nineteen twentieths of all the evangelical churches in this country believe that there is such a thing as being ‘born again,’ ‘born of the Spirit’,” Baird insisted. “And very few, indeed, admit the doctrine that a man who is not ‘converted,’ that is, ‘renewed by the Spirit,’ may come without sin to that holy ordinance.” Prospective members would testify to “the history of the work of grace in their hearts, and give their reasons for believing that they have become ‘new creatures in Christ Jesus’.” Often they would be quizzed by the pastor or a group of elders:

If the person who applies to be received as a member of the church is a stranger, or one of whose deep seriousness the pastor and the brethren of the church had been ignorant, then he is examined more fully upon his “experience,” or the work of God in his soul. He is asked to tell when and how he became concerned for his salvation, the nature and depth of his repentance, his views of sin, his faith in Christ, his hopes of eternal life, &c., &c. These examinations are sometimes long, and in the highest degree interesting.

In a footnote, Baird even suggested a 10-point summary of “faith and covenant” that prospective members could stand “in the midst of the church” and read aloud.20 While many Swedes were used to the idea of conversion and spiritual rebirth, this kind of public testimony was not in their comfort zone.

Much of the difference, to a 21st-century observer, seems to have been cultural. In his history of home missions, Colin Brummitt Goodykoontz rather delicately suggests 19th-century religious publications sometimes feared “that continental habits of Sunday observance would overthrow the Puritan Sabbath, and that German rationalism and infidelity would undermine revealed religion.” Chicago’s Pastor Andersen, in fact, was a staunch foe of German theological innovations; but, as we have seen, Sabbath observance was problematical for his Scandinavian parishioners.21 In Sweden and Norway all were baptized into the state church, catechized or instructed in its basic tenants and confirmed or admitted to its sacraments as youngsters. That was standard procedure for Lutherans, and had been since the 1520s when Martin Luther and John the Steadfast, elector of Saxony, worked out the basic arrangement. Public testimony about private struggles didn’t enter into it.

Thus a certain amount of conflict was almost inevitable when Swedish pastors accepted help from the AHMS, reflecting the very different historical and cultural backgrounds of 19th-century Protestants from America and northern Europe. Storm clouds began to scud up early. When Esbjörn was notified in January 1850 that the American Home Missionary Society had granted a $300 stipend, he was admonished:

We desire that you particularly pay attention to promote an evangelical teaching, the necessity of a new birth through God’s Spirit, and not to receive as members in the congregations or admit to the Lord’s Supper, any who are not able to give evidence of a new birth. Some of our German and Lutheran churches are quite loose on this point in that they follow their method of receiving members into a congregation through confirmation. Those who support this Society are quite determined in this matter … 22

Behind the AHMS policy was the evangelical doctrine, ultimately derived from the Calvinism of Puritan New England, that restricted church membership to an elect who could prove they were chosen for salvation. This doctrine did not die out with the first generation of sixteenth-century Calvinists; indeed, it was, as Baird insisted, normative in the mid-19th century.

As Garry Wills suggests in Head and Heart, the Calvinist theology behind it was intricately bound up with the American ideal of separation of church and state, or, in Roger Williams’ words, a “hedge or wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world.”23 Williams argues that the “church of the Jews under the Old Testament and the church of the Christians under the New Testament … were both separate from the world,” but when the early church became the established religion of the Roman Empire in the 300s, it lost its light of divine truth, which he likens to a candlestick. Mixing his metaphors with abandon, he argues that when:

… they have opened a gap in the hedge or wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world, God hath ever broke down the wall itself, removed the candlestick, and made his garden a wilderness, as at this day. And that therefore if He will ever please to restore His garden and paradise again, it must of necessity be walled in peculiarly unto Himself from the world; and that all that shall be saved out of the world are to be transplanted out of the wilderness of the world, and added unto His church or garden.23

While Williams is regarded, with some justice, as the first prophet of the freedom of religion, he had an almost obsessive fear of blighting the garden with the non-elect, or unconverted. Wills notes in an aside that Williams “always had trouble finding people pure enough to pray with – his enemies could never make out whether that meant he prayed only with his wife or not even with her. They were certain it precluded him from grace before meals except when he dined alone.”24 But Williams’ differences with orthodox Puritans were matters of degree, not of kind, and the idea that non-believers were not to be allowed in the church would become normative over the years. To this was added the idea that the church was a body of pure believers who joined in a compact, or covenant, with God and with each other to worship together and teach right doctrine.25 The Puritan ideal was still very much in the background when Swedish Lutherans came to organize churches in America.

Frances FitzGerald suggests that the ideal of “close-knit communities … bound by a covenant, where church and state cooperated in an effort to build a Holy Commonwealth,” had evolved into a “folk religion” that by the mid-19th century was normative in Protestant America. “Calvinism formed the backdrop to this system,” she says, “but key doctrines, such as irresistible grace, limited atonement, and unconditional election, played no part in it.” Instead, it relied on hellfire-and-brimstone sermons leading up to an emotional conversion experience – a “new birth” or “sudden experience of God’s grace,” followed by participation in “a church community that taught moral discipline.” FitzGerald adds that this kind of conversion “was a social act in that it entailed joining a church, abiding by its standards, and becoming a role model for others, but the society thus conceived was a small one.”26

Creolization: ‘A bit of this, a bit of that’

On Nov. 23, 1850, a prospective theology student from Sweden named Eric Norelius arrived at Andover in a heavy snowstorm. There he had “expected to find at least a fair-sized village, since Esbjörn had a functioning parish there, “but to our disappointment, it was an open prairie with a house here and there.” The next day he looked up the pastor, who would become his lifelong friend and mentor. “Esbjörn was dressed in a ragged old Swedish clerical coat. Everything in the house testified to great poverty,” he recalled in later years. The pastor was busy “teaching geometry to two young ladies of American birth,” but he invited Norelius to stay for a supper of buttermilk and cornmeal mush. “I had never in my life tasted sour milk,” said Norelius, “and I would rather have faced a bear than to eat sour milk.” But he stayed for supper, and that evening they found time to talk of “both temporal and spiritual matters.” Esbjörn was “pious, friendly, sympathetic, and serious,” and he promised to help Norelius get a theological education, something he couldn’t afford in the old country.27 In later years, Esbjörn and Norelius would be among the founders of the Augustana Lutheran Synod, and Norelius would serve as its president and still later become its first historian.

By the autumn of 1850, Esbjörn had been in Andover about a year, and he was well into the process of establishing there a Swedish-style parish, a regional unit comprising congregations in several locations including Moline and Galesburg as well as his home congregation. It was quite a bit different from an old-country parish, though. It received no government support, it was an independent congregation, governed by its pastor and a somewhat informal group of deacons instead of reporting to a bishop or archbishop as in Sweden; and it scraped along on what little money its recent immigrant parishioners could raise. Hence Esbjörn’s ragged coat and supper of cornmeal mush.

In significant ways the parish in Andover was more like what old-country Swedes called a “conventicle” than a state-church parish. These were informal meetings of like-minded lay people, often known as läsare (readers), who read scripture, sang pietistic gospel songs not in the official psalmbook and encouraged each other to lead what they considered godly lives. Esbjörn was a staunch pietist, and he had encouraged such meetings in the old country – even though they were technically against a seldom-enforced 1726 law forbidding them.28 Thus, partly by choice and partly because he had no ready alternative, he adopted a congregational church organization very similar to the congregational polity espoused by the American Home Missionary Society.

Writing in 1908 when early settlers were still alive to share their reminiscences, a Swedish-American historian named Ernst Olson found other correspondences as well:

His dependence on the American Congregationalists as well as the fact that he was surrounded by Methodists who lost no opportunity to decry everything that savored of the Swedish state church, caused Esbjörn gradually to accommodate himself to the Reformed order of service to the extent of discarding for a time certain portions of the Swedish church ritual as well as the use of the Pericopes [assigned readings for the day]. … His departure from those practices under the circumstances should not be too severely judged. It was the result more of necessity than of inclination. He was never a noisy revivalist, his religious convictions and Christian experiences being deeper and more temperate than those of his puritanical American associates.29

Swedish Lutheran immigrants tended to lump American Protestants together as “Reformed,” seeing few distinctions between Methodists, frontier Baptists, Congregationalists and Presbyterians. Down in Galesburg, the Rev. T.N. Hasselquist arrived from Sweden and took over from Esbjörn in 1852. In later years he would uphold Lutheran traditions as president of the Augustana Synod, but at first he ditched the prästkrage, or clerical collar of an ordained minister of the Church of Sweden, and with it much of the Swedish liturgy. In an undated reminiscence, Eric Norelius would later recall:

On a Sunday morning one could see him come into the church dressed in a white linen duster, and as he walked up the aisle, he would begin singing one of [Swedish pietist gospel singer Oscar] Ahnfeld’s songs and the congregation would usually chime in. Then he would stalk straight up into the pulpit, read a passage of scripture, utter an extemporaneous prayer, and then preach for a while; but just as he was preaching, he would begin singing some familiar hymn, after which he would continue his sermon. The conclusion was as improvised at the beginning.

This kind of thing struck some Swedes as too much of a concession. Norelius would later accuse the first immigrants of a “timid and thoughtless yielding to the American Reformed-Puritan sects by which the newcomers were surrounded and influenced.”30 Even in the 1850s, as more parishioners arrived from Sweden, their pastors would turn back to their confessional and cultural roots. In the winter of 1850, however, Esbjörn faced a more immediate challenge.

In June 1849 Esbjörn had emigrated with a party of 146 from north central Sweden, 47 of them from his own parish in Sweden. On the journey, he came down with cholera and remained in Chicago while the rest of the party went on without him. By the time he got to Andover late in October, only a few remained there. Many, including two of Esbjörn’s children, had died en route; others were persuaded by the Rev. Jonas Hedstrom, a nearby Methodist minister, to relocate to a Swedish settlement east of Galesburg where he had a church. Hedstrom, who by most accounts was an inspiring revivalist preacher and a devoted evangelist, was to be a thorn in Esbjörn’s side.31 While the Swede had corresponded with Hedstrom and expected to work closely with the Methodists in America, he was not at all prepared for an American style of evangelism that looked to him like rank proselytizing. Other problems emerged quickly.

Esbjörn had secured funding to the tune of $300 a year from the American Home Missionary Society, and he was committed to their ideal of a gathered community of saints. Back in Sweden he’d had his own conversion experience, at a temperance meeting in August 1840, and something very much like the English nonconformist, or Puritan, concept of a gathered community was part of the pietist movement. Lars Österlin of Lund University explains:

It was not the intention of the Pietists to break out of the Lutheran confessional and ecclesiastical community. But they were disenchanted with a church tradition which, as they saw it, was superficial and formal. According to them, every individual had to have an inner experience of faith, and then to be changed, in order to show true seriousness in his Christian life. It was not enough, then, to have been baptized and to observe the external practices of church life. There had to be a spiritual breakthrough. In their view, there was a clear distinction between the truly faithful and the rest, who were merely Christians out of habit. As a result – and this is where the real problem lay – real church fellowship, in the Pietist view, was not that of the national church or the parish, but that of the group of believers. This concept was potentially explosive.32

For Esbjörn, trying to organize a parish out on the Illinois prairie in the winter of 1850, the concept wasn’t so much explosive as daunting. The problem was, there weren’t that many saints in Andover. When the time came on March 18 to create an “evangelical Lutheran congregation” there, as Esbjörn would later report to clergy of the Swedish archdiocese of Uppsala, he had only 10 prospective members he considered worthy of joining the congregation, and “though I had a bound Church Records book with me from Sweden, trouble makers had made so much of the fear of the ‘State Church bonds and fetters’ that I did not dare to bring it out and enter the names.”33 The situation was unsustainable.

Even before the organizational meeting in Andover, Esbjörn and Andersen were taking steps to modify the stricture “not to receive as members in the congregations or admit to the Lord’s Supper, any who are not able to give evidence of a new birth.” Already in his quarterly report to the Home Missionary Association, dated Feb. 28, Esbjörn said he had consulted with Andersen in December, soon after he arrived in Andover:

[Andersen] said that occasionally he felt compelled to admit Scandinavians to the Holy Supper, though they were not members of any American church, when they expressed a sincere desire for it, promised to use the Word of God and to pray for their conversion, and on the basis of their having been members of the State church at home were not to be compared with those in this country who stand outside the church.

Accordingly, Esbjörn had celebrated communion after “first speaking privately with each of the communicants and exhorting all who I deemed unconverted to repent and pray for conversion.” Some promised to do so, and others he “persuaded … to wait with communion.” In the absence of further instructions, he advised AHMA, “I shall follow this plan ad interim and provisionally under present circumstances.”34 Although they would be modified as more immigrants came to Illinois, the essentials of Esbjörn’s plan would serve as an interim membership policy for the Swedish and Norwegian congregations that banded together, first in 1852 as ethnic Lutheran churches belonging to a regional conference of the nationwide General Synod and in 1860 as they created the Augustana Evangelical Lutheran Synod.

A hundred years later Conrad Bergendoff, a historian, theologian and longtime president of Augustana College, returned to Esbjörn’s dilemma in a series of lectures on the “Doctrine of the Church.” Esbjörn, he suggested, “found in America a kind of church activity which challenged fundamental Lutheran doctrines.” Chief among them was not undermining the Lutheran “doctrine of the new birth in infant baptism” by giving in to American revivalists’ demand for adult conversion. Esbjörn, like other pietists back in Sweden, maintained that a “Christian life should show forth a Christian faith.” But American frontier revivals were something entirely new to his experience, and Bergendoff suggests the problem went beyond their emotionalism: Whereas infant baptism was the key to membership in Lutheran lands, in the American Protestant groups it was often necessary to validate one’s right to be called a Christian. One should be able to decide to become a Christian, and the churches provided the means of decision in the revival system. One should be able to point to a date of conversion.35

Baptism and communion were the fundamental Lutheran sacraments, and it was to be a recurring problem, In the spring of 1850, however, Andersen and Esbjörn came up with a creolized hotchpotch, a bit of this and a bit of that, a mélange that satisfied continental Lutheran and American revivalist expectations, at least for the time being.

Bit by bit, the Swedish colonies in Chicago and western Illinois began to grow. In his next quarterly report on May 27, Esbjörn noted, “one person after another has come, acknowledging and confessing themselves as helpless sinners, hungering and thirsting for the righteousness of Christ, and joined our congregation through a public declaration.” They nearly tripled the size of the congregation. He had also begun “promising Sabbath schools,” an American innovation, in Andover and Galesburg. The following year a Swedish Lutheran congregation was organized in Galesburg, with Esbjörn serving both communities until October 1852 when Hasselquist came to town.

On his way out to the prairie, Hasselquist met Pastor Andersen in Chicago and promised to return to help organize a Swedish congregation in the city. That he did, and in a service in the Norwegian church on Jan. 17, 1853, Hasselquist “preached on Christian caution with regard to unfamiliar religious bodies,” and Andersen “offered a gripping prayer which brought tears to the eyes of most.” They sang a hymn from the Swedish psalmbook, “O Gud! ditt ord och sakrament / Låt aldrig bliva från oss vändt” (O God, let your word and sacrament never be taken from us), and the new Swedish congregation was thereby spun off from Andersen’s predominantly Norwegian church.36 Soon to be named Immanuel Lutheran Church, it has continued to the present on the North Side of Chicago.

The same day, Hasselquist wrote to a missionary society in Sweden asking that an ordained minister be sent to Chicago. Pastor Carlsson answered the call, and on Aug. 28 he preached his first sermon there.

Carlsson was more formal than Esbjörn or Hasselquist. To the great relief of some of his parishioners in Chicago, he hewed closer to the Swedish liturgy than his colleagues and wore Swedish clerical garb including the prästkrage that Esbjörn and Hasselquist had abandoned out on the prairie. Once when Carlsson preached in Andover, according to an eyewitness, “the aged peasant women wept and said to each other so loudly that we could hear them, ‘Praise God that once again we are permitted to see and hear a pastor with a ministerial collar’.” Eric Norelius, who by that time was studying theology at a German Lutheran seminary in Ohio, attended Carlsson’s service on a visit to Chicago in September, and he was bowled over. “It was a wonderfully precious hour,” he said, “when I could take part in a Swedish Lutheran service and hear a good, doctrinal sermon in the Swedish language, after being without this great privilege for three years.”37 Carlsson’s gifts were also administrative, and he set about drafting a constitution for the congregation, a chore that had been neglected up to that time.

Ratified in January 1854, the constitution expanded on Esbjörn’s formula. The minutes of that meeting state:

As to the receiving of new members it was resolved that no one should be accepted in the congregation who has been or is known as guilty of an un-Christian and wicked life. Those who wish to unite with the congregation should make this known to the pastor, who through personal interview and in consultation with the church council will inform himself of the applicants’ Christian faith and moral character.38

Thus, with a bit of this and a bit of that, newness entered the world. The policy statement was consistent with American evangelical Protestant and Swedish pietist theology – the church ought to be a believers’ assembly – but to it Carlsson added a leavening of Swedish reticence and a reference to basic Lutheran doctrine as formulated for the Diet of Augsburg in 1530. When new immigrants from Sweden were received as members, they would stand at the altar while the pastor asked:

Dear friends, you have asked to become members of this our Evangelical Lutheran congregation. Since you have been born and nourished within the Lutheran Church we do not require any new profession of faith. We desire only to know if also in this land you will remain true to our ancient unforgettable faith and teaching. On behalf of the congregation I therefore ask if with sincerity of heart you will faithfully adhere to the Confession you have already made at the altar of the Lord (in confirmation), and accordingly will hold to the unaltered Augsburg Confession?

In essence, this language wrote Andersen’s and Esbjörn’s compromise into the bylaws of the new Swedish congregation.39 It would serve its purpose for decades.

In later years Eric Norelius, who became a licensed minister in 1856 and went on to serve as president of the Augustana Synod and write its first histories, would note that Carlsson’s formulation of the compromise, “with few alterations is almost word for word the one adopted by Synod 10 years later at the Rockford Convention and used in all our congregations.” Reminiscing during the 1880s in a synodical magazine called Korsbaneret (the banner of the cross), Carlsson said it “provided a golden mean between the inclusiveness of the State Church of Sweden and the sect’s attempts to establish on earth congregations of true believers.” Emory Lindquist, Carlsson’s biographer, adds that it “emphasized the concept of a folk församling (a people’s congregation) in contrast with a ren församling (a pure congregation of believers)” like those considered normative by evangelical Protestant churches (Carlsson considered them sects) of the mid-19th century in America.40

It also served as a “golden mean” when the Swedes helped craft a membership policy for the Synod of Northern Illinois, an umbrella organization for Americanized German and Scandinavian Lutheran churches formed in 1851. Oscar Olson, a mid-20th century historian of the pioneer days of the Swedish- American synod, says the issue was controversial, in part because “the Germans and the Norwegian Synod were satisfied to accept members on the basis of confirmation, while the Swedish churches and some other Lutherans required confession of conversion and Christian life as a condition for membership.” The question remained in a committee, chaired by Esbjörn, until 1854 when the synod’s Chicago-Mississippi Conference recorded in its minutes:

In regard to members baptized and confirmed in the homeland who are to be received into our congregations, it did not seem quite proper to require again an avowal of faith which they had already given, and thus confirm them, as it were, anew. Instead it was decided only to inquire of them, if they intend faithfully to adhere to the Confession which they already have given at the altar of the Lord, and accordingly to hold fast faithfully to the Augsburg Confession, and to observe seriously those duties to which this Confession in general and membership in a congregation in particular binds them. It was left to each congregation to state these questions as it wished. The formula which had been used by Br. Andersen in Chicago seemed especially suitable and worthy of recommendation.41

While the historical record isn’t entirely clear about the details, Carlsson’s “golden mean” may have helped get Immanuel Lutheran’s church council out of a jam back in Chicago. The published version of its minutes for Thursday, May 28, 1857, drily records, with the names left blank, that:

A request to become a member of the congregation had … been received from _____ __________, and though he had handed a certificate to the Church Council from Justice J.L. Miliken stating that _____ __________ because of insufficient evidence had been acknowledged innocent of the charge preferred against him by _____ __________: nevertheless the Church Council felt that this matter as well as the status of _____ __________ in general were of such a nature that it is unwilling to be responsible for accepting him as a member of the congregation; but resolved that the question be submitted to a vote of the congregation itself, and that this vote be taken tomorrow evening after the close of the service and the reading of these minutes.

Meeting after Friday vespers, the congregation voted 26-15 not to admit “_____ __________.”42 Whoever he was and whatever the charges against him might have been, Carlsson’s compromise came in handy.

In the meantime, Esbjörn was having second thoughts about the whole matter. On Jan. 30, 1856, he wrote Norelius, who by that time had finished divinity school and was a pastor in Minnesota, acknowledging his views had changed since “the time I was – what shall I say – more Methodistic in my religious views” when he first came to America:

After I attained greater clarity in the gospel and know that in Christendom the new birth takes place in baptism and not really in the conversion of the sinner in adult years, I have been liberated from those views. I now believe in truth that many a one arises in all silence, without external (Reformed) noise and bluster, and goes to the Father, confesses his sin and receives the festive garment, etc., and thus many who by the ordinary Reformed, “läsare,” (“readers”), yardstick are counted only as “honorable and naturally decent persons,” are still at heart among the faithful, though they may not be as talkative about it.

As Esbjörn’s biographer Sam Rönnegård points out, “Methodistic” in this context has very little, if anything, to do with Methodist doctrine. And “Reformed” is similarly unrepresentative of what Calvinist churches of the day would recognize as good doctrine. Perhaps we can put it down to experience, perhaps to Lutheran practice, but Esbjörn noted:

… we often err in our judgment as to who are the faithful, and who are not. Furthermore we need to remember that the Lutheran church teaches us to consider each one as good (since in baptism he has become a child of God) until the opposite is proved, whereas it follows from the Reformed doctrines that each one is accounted evil until he proves the opposite.43

We can look back at this 150 years later and surmise that Esbjörn was reacting more to what he considered the excesses of frontier evangelism, camp meeting pyrotechnics and his experience with Methodist and Baptist proselytizers in western Illinois than he was to Reformed theology. His aversion to “noise and bluster” sounds, with a century and a half of perspective, more cultural than religious.

But Esbjörn’s discomfort had a theological underpinning that goes back to Luther: The American evangelical stress on adult conversion, as Bergendoff points out, undermined the Lutheran practice of infant baptism, and Luther had been adamant about that. He was also adamantly opposed to the whole idea of a gathered church of pure believers. Copies of the reformer’s sermons were widely available in Europe and in America, and Esbjörn – who had a scholarly streak – well could have read this passage regarding Luther’s attacks on the Anabaptists of his era in Swiss Protestant scholar J.H. Merle d’Aubigné’s History of the Great Reformation of the Sixteenth Century, a popular work that was published in translation in Philadelphia in 1844:

“The Sacred Writings,” said Luther, “were treated by them as a dead letter, and their cry was, ‘The Spirit! The Spirit!’ But assuredly, I, for one, will not follow whither their spirit is leading them! May God, in His mercy, preserve me from a Church in which there are only such saints. I wish to be in fellowship with the humble, the weak, the sick, who know and feel their sin, and sigh and cry continually to God from the bottom of their hearts to obtain comfort and deliverance.44

Luther was very clear on the point, and it was quite the opposite of a pure church limited to saints and believers.

‘The children learn English easily in that country’

In 1856, Esbjörn moved on from Andover. As immigration continued to increase, he and his colleagues were no longer able to recruit enough ordained pastors from Sweden to fill the newly established pulpits. So they lobbied the Synod of Northern Illinois for a “Scandinavian professor” at its seminary in Springfield, and in 1857 Esbjörn joined its faculty. There he taught until he resigned in 1860 over doctrinal issues and the Scandinavians pulled out of the multi-ethnic synod to form their own Augustana Synod (so named for a foundational Lutheran document called the Confessio Augustana or Augsburg Confession). From 1860 to 1863 he was the president – and sole instructor – of what would become Augustana Theological Seminary, meeting initially in the basement of the Norwegian church in Chicago.

In 1863 when Esbjörn was back in Sweden on a fund-raising trip, the pulpit at his old parish in Östervåla came open; he took the position, and there he plunged into the duties of an old-country Swedish parish priest and earned a lasting reputation for helping establish the public schools in his area.45 In 1865 at a meeting of clergy in the archdiocese of Uppsala, he delivered a lengthy report on the Swedish Lutheranchurches in America. In an aside, he told the story:

… of a Swedish boy, who had, without permission, gotten into his mother’s baked goods. When she admonished him, he answered: “Why mother, isn’t this a free country?” The Swedish children learn English easily in that country.46

Swedes in this country, Esbjörn added, also learned the value of compromise. In America, he said, an immigrant pastor “in many cases could, by appropriate modification, preserve and even clarify doctrine and turn aside the storms which arise so easily in a land with unlimited religious freedom.”

Some of these modifications, he said, were liturgical; others were dictated by the practice of Protestant churches in America. And membership policy, he acknowledged, was very specifically dictated by AHMS policy and Esbjörn’s supervisors in the Illinois Congregational Association of Galesburg. Compromise clearly was needed. On the one hand, he told the clerics gathered in Uppsala:

Experience soon showed that this requirement on paper created difficulties in practice, especially since it was easy for fanatical opponents to the Lutheran church to awaken emotions which expressed themselves in the requested confession, and it was clear enough in all bodies, that many who joined the congregations easily learned to use the required language [claiming a conversion experience]. Furthermore, many of our Swedes arriving in America were already members of the Lutheran church, and could not be seen as now making their first entry into it.

On the other hand, he was grateful to the AHMS for its financial assistance. “It should also be added, to the Illinois Congregational Association’s credit, that, despite my full and free presentation of my and the Lutheran church’s beliefs and teaching on the sacraments, grace, fall from grace, etc., at their meeting, they never sought to convince me or any of my people to leave the Lutheran Church, since my righteous and frank presentation of my personal experience convinced them that I wished to work to establish a true and living Christianity among our people.” Moreover, he accepted the idea that “it was not advisable nor conscientious to immediately accept every unknown person who came from Sweden with their pastor’s letter of parish registration,” especially in a new land where conditions were very different. So Esbjörn outlined the compromise in detail and concluded:

Hereby, one recognizes confirmation and membership in the church in Sweden, and receives the only guarantee of the member’s Lutheran orthodoxy and proper behavior as a member of the church that can be found in a land where all possible beliefs and opinions are equal, and where congregational governance and discipline are not dependent on worldly power. Esbjörn said “a dozen years’ experience has shown us [the compromise] was successful.”47

It would last longer than 12 years. As we have seen, Esbjörn’s compromise formed the basis for membership policies of the Northern Illinois Synod and the Augustana Synod as well. Granted, it didn’t settle the issue. In 1869 and well into the 1870s, a split would occur when pietist Swedes in Kansas insisted on a pure church of believers instead of a national, or ethnic, church (folk församling in Swedish); many of the Kansans would return to the Augustana fold, but other pietists would soon leave the synod to form the Mission Friends and, still later, the Evangelical Covenant Church.48 Even so, the center held.

This was part of a larger trend, especially after the American Civil War as Scandinavian and German immigrants brought a more European brand of Lutheran practice with them, less oriented to the evangelism of frontier camp meetings. In his survey The Old Religion in a New World, evangelical historian Mark A Noll says the trajectory of Esbjörn’s career typifies the trend toward confessional orthodoxy:

Fourteen years after Esbjörn came to America, he returned to Sweden, where he accepted a position in the established Lutheran Church, the very church he had once abandoned as hopelessly corrupt. For Esbjörn, the transplantation of Christianity from Europe to America meant at first unprecedented opportunity to advance an activist pietism, then growing concern about the excesses of American liberty, and finally a return to traditional European institutions.

In 1850 American Lutherans, most of them under the same General Synod umbrella as the Synod of Northern Illinois, were largely assimilated. As Noll remarks cleverly (and not inaccurately), the Americans advocated what they “thought was a pious form of Americanized Lutheranism but [their] detractors concluded was only a mildly Lutheranized form of American pietism.” Esbjörn was not the only immigrant to return to his confessional roots.

Noll hypothesizes that as the immigrants formed new ethnic synods, American “Lutherans lost influence with the public at large, promoted a parochial spirit, strengthened their dependency on the memory of Europe, and rejected the lessons of an active, hundred-year tradition of negotiating a livable compromise between Old World traditions and New World realities.”49 While his point has considerable merit, I believe it can also be argued that immigrants like the Swedes, by returning to their confessional roots, helped point the way to greater religious diversity in the 20th century. Other Lutheran immigrants split into ethnic synods – including at least four Norwegian groups that squabbled over doctrine, as well as Finns, Slovenians, Icelanders and both “happy” and “gloomy” Danes (the latter being more pietistic). The Missouri Synod, made up of Germans who came to America largely because they rejected union with the Reformed churches of Germany, also aligned itself along ethnic and confessional lines. At the same time, German, Irish and later Italian Catholic parishes were forming in the cities. The historical trend was toward diversity, as different ethnic groups negotiated the differences between old and new worlds.

In this vein, James D. Bratt, who spoke at the Augustana Heritage meeting in 2012, suggests that acculturation is negotiated between “two countervailing forces,” which he defines as “the continuing power of inherited traditions rooted abroad and the unexpected turns these traditions can take, the interesting consequences that ensue, when inheritance enters a new environment.” Instead of a more-or- less binary process of assimilation to American norms, he suggests a more nuanced approach that takes into account the diversity of immigrant groups:

The bottom line … was expressed well 120 years ago by one of my own Dutch immigrant subjects: “We are not and will not be a pretty little piece of paper upon which America can write whatever it pleases.” Acculturation is a two-way, not a one-way, street. We read the same lesson in the annals of Norwegian and German immigration, among Jews and Catholics of various national origins, and also in Maria Erling and Mark Granquist’s history of Augustana. A good many people in all these groups came to the United States looking not so much to find a new way of life as to preserve an old one.

The result, according to Swedish historian Ulf Beijbom, was an Augustana Synod comprising a hybrid of the old world and the new. “This organization,” he says, “can be described as a reformed offshoot of the Church of Sweden in which the early demands for conversion were modified by the idea of a ‘people’s church’ open to all Swedish immigrants and in which abolition of the episcopacy satisfied the revival influenced nucleus of the synod.” In this, Bratt and Beijbom alike come close to the cultural anthropologists who speak of creolization. In later years, Swedish-Americans would pride themselves on how rapidly they assimilated. But in actuality, the process was more complex.50 Seeing it instead through the lens of acculturation and creolization offers us a more nuanced picture of how American culture evolved and how it might evolve in the future.

In quite a different context, folklorist James Leary suggests the multi-ethnic dance bands of the 1940s and 1950s in the upper Midwest created a “creolized, regional repertoire” out of Norwegian, Swedish, German, Slavic and “Scandihoovian” musical licks. “Here,” he proclaims, “reside North Coast creoles.” I am sure that L.P. Esbjörn, Paul Andersen and Erland Carlsson would have horrified by “polkabilly” dance music. But I would argue that their ethnic congregations of the 1850s created hybrid forms, in Ulf Hannerz’ words, that “put things together in new ways” and brought something new into the world. In other words, the Swedes, like so many other immigrants, rejoiced in mongrelization, mélange, hotchpotch, a bit of this and a bit of that.

NOTES

1. Andersen, Report to the American Home Missionary Society, April 1, 1850,” Augustana Historical Society Publications, 5 (1935): 51-52; Jens Christian Roseland, American Lutheran Biographies: Or, Historical Notices of Over Three Hundred and Fifty Leading Men of the American Lutheran Church, from Its Establishment to the Year 1890. (Milwaukee: A. Houtkamp & Son, 1890), 25-29 [Google Books]. Andersen spelled his name variously, including on reports he submitted to the AHMS. I follow the spelling used by Bergendoff and other historians of the Augustana Synod.

2. Sweden and Norway were a joint monarchy, ruled in 1850 by Swedish King Oscar I. Their established churches in Scandinavia were separate, but both were Lutheran; Swedish and Norwegian immigrants often cooperated in the early days of immigration from Scandinavia.

3. Esbjörn’s report to AHMS, Feb. 28, 1850, is quoted in Eric Norelius, The Pioneer Swedish Settlements and Swedish Lutheran Churches in America, 1845-1860, trans. Conrad Bergendoff (Rock Island: Augustana Historical Society, 1984), 81.

4. Creolization is discussed at greater length in my article “‘How Newness Enters the World’: Cultural Creolization in Swedish-American Hymnals Published at Augustana College, 1901-1925,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 109 no. 1 (Spring 2016): 9-14, 33-38.

5. Peter J. Guarnaccia and Carolina Hausmann-Stabile. “Acculturation and Its Discontents: A Case for Bringing Anthropology Back into the Conversation,” Sociology and Anthropology, 4 no. 2 (February 2016): 115-16, n122; James D. Bratt, “The Augustana Synod in Light of American Immigration History,”Augustana Heritage Newsletter, 8 no. 1 (Fall 2012): 12-13.

6. Ulf Hannerz, Cultural Complexity: Studies in the Social Organization of Meaning (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 264–65; he quotes Rushdie in Transnational Connections: Culture, People, Places (London: Routledge, 2002), 65–66 [italics in the original]. See Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Globalization and Culture: Global Mélange (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009), 125.

7. See Andrei A. Znamenski, trans., Through Orthodox Eyes: Russian Missionary Narratives of Travels to the Dena’ina and Ahtna, 1850s-1930s (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2003), p 6; Roxanne Easley, “Creole Policy and Practice in Russian America” (paper presented at History and Heritage of Russian America Conference, Moscow, April 13-14, 2016), reprint, Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington, Seattle https://depts.washington.edu/cspn/creole-policy-and-practice-in- russian-america-iakov-egorovich-netsvetov/; James P. Leary, Polkabilly: How the Goose Island Ramblers Redefined American Folk Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 12-13, 17.

8. Norelius, Pioneer Settlements, 71-75, 81-85; Sam Rönnegård, Prairie Shepherd: Lars Paul Esbjörn and the Beginnings of the Augustana Lutheran Church, trans. G. Everett Arden (Rock Island: Augustana Book Concern, 1952), 112-21. See also Conrad Bergendoff, The Doctrine of the Church in American Lutheranism (Philadelphia: Board of Publication, United Lutheran Church of America, 1956), 50-55.

9. Garry Wills, Head and Heart: American Christianities, (New York: Penguin Press, 2007), 54-75. 93-99; Diarmaid MacCulloch, Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (New York: Penguin, 2009), 764-65. In my understanding of the broad sweep of American religious history, and the place of 19th-century Swedish immigrants in it, I am heavily indebted to Wills and MacCulloch alike. In addition to contemporary accounts of the Swedish immigrant churches, I rely especially on Oscar N. Olson, The Augustana Lutheran Church in America: Pioneer Period, 1846-1860 (Rock Island: Augustana Book Concern, 1950), 48-92; and Maria Erling and Mark Granquist, The Augustana Story: Shaping Lutheran Identity in North America (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2008).

10. Bratt, “Augustana,” 13.

11. See especially Dag Blanck, The Creation of an Ethnic Identity: Being Swedish American in the Augustana Synod, 1860-1917 (Southern Illinois University Press. 2006), 162-64, 188-94; Thomas Tredway, Conrad Bergendoff’s Faith and Work: A Swedish-American Lutheran, 1895-1997 (Rock Island: Augustana Historical Society, 2014), 15-19, 135-49.

12. Erland Carlsson, “Some Advice and Information for Immigrants to the United States of America,” trans. O.V. Anderson; reprinted as an appendix to Emory Lindquist, Shepherd of an Immigrant People: The Story of Erland Carlsson (Rock Island: Augustana Historical Society, 1978), 213, 216.

13. Ulf Beijbom, Swedes in Chicago: A Demographic and Social Study of the 1846-1880 Immigration, trans. Donald Brown (Uppsala: Läromedelsförlagen, 1971), p. 62; Lindquist, Carlsson, 30-31; Rönnegård, Prairie Shepherd, 179-91; John Lewis Peyton, “Seeing Chicago from a ‘Trap’,” in Bessie Louise Pierce, ed., As Others See Chicago: Impressions of Visitors, 1973-1933 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 101. Cf. Erika K. Jackson, Scandinavians in Chicago: The Origins of White Privilege in Modern America (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2019), 18-34.

14. My overview of Swedish immigrant communities is pieced together from Beijbom, 57-63; Oscar Olson, Pioneer Period, 48-92; and Erling and Granquist, Augustana, 8-28.

15. Joseph C.G. Kennedy, Population of the United States in 1860; Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864), xxviii-xxvix https://archive.org/details/populationofusin00kennrich/page/n39/mode/2up; Fredrika Bremer, “Prairies,” in Pierce, As Others See Chicago, 131. See also Lars Ljungmark, Swedish Exodus, trans. Kermit B. Westerberg (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1979), 10-13; Dag Blanck, The Creation of an Ethnic Identity: Being Swedish American in the Augustana Synod, 1860-1917 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois Press, 2006), 30.

16. Timothy L. Smith compiled membership numbers for 1855 and 1865, and discussed the influence of Lutheran “new measures” in Revivalism and Social Reform: American Protestantism on the Eve of the Civil War (2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980), 20-21, 30-31, Cf. Mark A Noll, The Old Religion in a New World (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 6-7. See also Norelius, Swedish Settlements, 126.

17. L.P. Esbjörn, “Report on the Development and Current State of the Swedish Lutheran Congregations in North America, Presented at the Clergy Meeting of the Upsala [sic] Archepiscopal See, 14 June 1865,” trans. John Norton,” in Augustana Historical Society Newsletter, (Spring 2009), 3; Rönnegård, Prairie Shepherd, 117-31, 179-96, 203-29. See also Beijbom, Swedes in Chicago, 39-56, 231-41; Erland and Granquist, Augustana, 22-27.

18. Smith, Revivalism, 21, 26-30, 39-40; L.H. Parker, Jonathan Blanchard and Eli Farnham to Milton Badger, Dec. 10, 1849, in Norelius, Swedish Settlements, 74-76; Colin Brummitt Goodykoontz, Home Missions on the American Frontier: With Particular Reference to the American Home Missionary Society (New York: Octagon, 1971), 173-91. See also Olson, Pioneer Period, 1846-1860, 37, 119, 229-31.

19. Robert Kolb and Carl R. Trueman, Between Wittenberg and Geneva: Lutheran and Reformed Theology in Conversation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2017), ix-x; Frances FitzGerald, in The Evangelicals; The Struggle to Shape America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 637-38. FitzGerald draws on an influential definition by British historian David Bebbington, and notes that “[m]any churches, Baptists and others, have some admixture of Calvinism in their theological make-up.” Immigrants are not the only Americans who rejoice in mongrelization, mélange, hotchpotch, a bit of this and a bit of that.

20. Robert Baird, Religion in America: Or an Account of the Origin, Relation to the State, and Present Condition of the Evangelical Churches in the United States (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1844), 140-41, 183-86, 186-87n.

21. Goodykoontz, Home Missions, 338; Baird, Religion in America, 257-60; Martin E. Marty, Pilgrims in Their Own Land: 500 Years of Religion in America (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1984), 173; Andersen, report to AHMS, March 31, 1849, Augustana Historical Society Publications, 5 (1935), 36.

22. Milton Badger to Esbjörn, Jan. 14, 1850, quoted in Norelius, Swedish Settlements, 78-79. See also Rönnegård, Prairie Shepherd, 138-50.

23. Wills, Head and Heart, 93-99, 273-75, 291-302.

24. John M. Barry, Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul: Church, State, and the Birth of Liberty (New York: Penguin, 2012), 196; Garry Wills, Under God: Religion and American Politics (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), 345, 350, 52-53, 418n11 [Wills’ italics omitted]; Edmund S. Morgan, Roger Williams: The Church and the State (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2007), 31. The enemies Wills cites were Puritan divine Cotton Mather and Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop.

25. See Barry, Roger Williams, 306-12; Perry Miller, Roger Williams: His Contribution to the American Tradition (New York: Atheneum, 1966), 98; Philip Hamburger, Separation of Church and State (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 48-50.

26. FitzGerald, Evangelicals, 14-20, 31-40, 54.

27. Eric Norelius, Early Life of Eric Norelius, 1833-1862, trans. Emeroy Johnson (Rock Island: Augustana Book Concern, 1934), 117-18.

28. Rönnegård, Prairie Shepherd 112-28; Norelius, Swedish Settlements, pp. 71-93. See also Bergendoff, Doctrine of the Church, 37-39; Nicholas Hope, German and Scandinavian Protestantism, 1700 to 1918, Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford: Clarendon, 1999), 372-78; and Lars Österlin, Churches of Northern Europe in Profile (Norwich, UK: Canterbury Press, 1995), 114-15, 153-59. The Konventikalplakat of 1726 was repealed in 1858.

29. Ernst Olson, History of the Swedes in Illinois (Engberg-Holmberg Publishing Co., 1908), 431.

30. Norelius, Swedish Settlements, 117-18, 126; Norelius’ reminiscence of Hasselquist’s preaching style, in an undated biography of Hasselquist published in Rock Island in 1900, is translated and quoted in G. Everett Arden, The School of the Prophets: The Background and History of Augustana Theological Seminary, 1860-1960 (Rock Island: Augustana Theological Seminary, 1960), 63, 272.

31. I rely on the accounts in Norelius, Swedish Settlements, 65-86, and Rönnegård, Prairie Shepherd, 84-116; both quote extensively from contemporary accounts. Ernst Olson, Swedes in Illinois, 423-34, has additional detail from Esbjörn’s family and other old settlers . Cf. Henry Carl Whyman, The Hedstroms and the Bethel Ship Saga: Methodist Influence on Swedish Religious Life (Carbondale: Southern IllinoisUniversity Press, 1992). I follow the Americanized version of Hedstrom’s name.

32. See Rönnegård, Prairie Shepherd, 19-39, 148-49; Österlin, Churches, 114.

33. Esbjörn, “Report at Clergy Meeting,” 4.

34. Milton Badger to Esbjörn, Jan. 14, 1850; Esbjörn to Badger, Feb. 28, 1850, quoted in Norelius, Swedish Settlements, 78, 81.

35. Bergendoff, Doctrine of the Church, 40-41.

36. Norelius, Swedish Settlements, 83, 118-19, 148-50.

37. Lindquist, Shepherd, 31-37.

38. Norelius, Early Life, 215; Rönnegård, Prairie Shepherd, 231.

39. Minutes of the Jan. 27, 1854, meeting are quoted in Norelius, Swedish Settlements, 158-59. Cf. I.O. Nothstein, trans., Selected Documents: Dealing with the Organization of the First Congregations and the First Conferences of the Augustana Synod and their Growth Until 1860, Vol. 2, Augustana Historical Society Publications, 11 (1946): 8-9.

40. Norelius, Swedish Settlements, 158-59; Lindquist, Shepherd, 34-36, 39n1. Lindquist believes Carlsson wrote the unsigned history of Immanuel in Korsbaneret.

41. Oscar Olson, Pioneer Period, 248-51; Nothstein, Selected Documents, Vol. 1, in Augustana HistoricalSociety Publications, 10 (1944): 92.

42. Minutes, May 28, May 29, and Dec. 19, 1857, in Nothstein, Selected Documents, Vol. 2, 19-20, 21.

43. Translated and quoted at length in Bergendoff, Doctrine of the Church, 39-40. Cf. the translation Rönnegård, Prairie Shepherd, 226.

44. J.H. Merle d’Aubigné, History of the Great Reformation of the Sixteenth Century in Germany, Switzerland, etc. (Philadelphia: James M. Campbell & Co., 1844), 321 [Google Books]; Bergendoff, Doctrine of the Church, 44.

45. Rönnegård, Prairie Shepherd, 239-91; the fullest account of Esbjörn’s academic career is in Arden, School of the Prophets, 87-103.

46. Esbjörn, “Report at Clergy Meeting,” 5.

47. Esbjörn, “Report at Clergy Meeting,” 5-6.

48. Lindquist, Shepherd, 35; Erling and Granquist, Augustana Story, 39-41, 53-56.

49. Noll, Old Religion, 6-7, 238-45. Cf. Nelson, Lutherans in North America, 147-99; Granquist, Lutherans inAmerica, 171-98.

50. Bratt, “Immigration History,” 12-13; Beijbom, Swedes in Chicago, 237-38; Jackson, Scandinavians, 136-47. Cf. Granquist, Lutherans in America, 183-88;

51. Leary, Polkabilly, 19-32.

[Uploaded March 3, 2024]