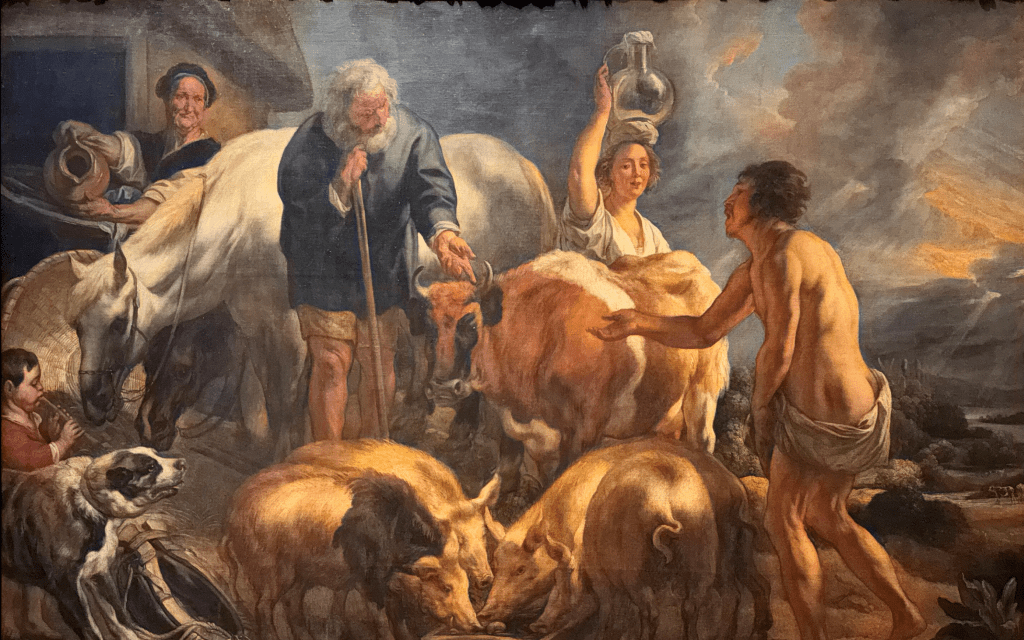

Luke 15:1-3, 11ff. (NRSVue). Now all the tax collectors and sinners were coming near to listen to him. 2 And the Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling and saying, “This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.” 3 So he told them this parable […]:11 “There was a man who had two sons. 12 The younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me the share of the wealth that will belong to me.’ So he divided h is assets between them. 13 A few days later the younger son gathered all he had and traveled to a distant region, and there he squandered his wealth in dissolute living. 14 When he had spent everything, a severe famine took place throughout that region, and he began to be in need. 15 So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that region, who sent him to his fields to feed the pigs. 16 He would gladly have filled his stomach[b] with the pods that the pigs were eating, and no one gave him anything. 17 But when he came to his senses he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired hands have bread enough and to spare, but here I am dying of hunger! 18 I will get up and go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; 19 I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.” ’ 20 So he set off and went to his father. […] — Common Lectionary, Year C, 4th Sunday in Lent (ELCA).

The Holy Spirit, I’ve decided, must have a quirky sense of humor. At the very least, the spirit knows how to get my attention.

A case in point: Recently when I was journaling on the story of the Prodigal Son — the one from Luke we all think we know — the spirit led me to fill out my ballot for Springfield’s April 1 school district and Capitol Township consolidated election and get it to a dropbox in time.

Not exactly what Jesus had in mind 1,992 years ago!

But that’s how the spirit operates with me. Instead of signs, wonders and sound doctrine, the spirit speaks to me in hints, whispers and, often enough, a nagging feeling that something isn’t quite adding up here, that I’d better think it over.

And that’s how I got from Jesus’ ministry in first-century Palestine to an off-year local election in central Illinois. With a couple of loops, U-turns and excursions down rabbit holes along the way, the spirit led me from a recent small-group discussion after church on Luke’s gospel to thoughts of today’s emerging resistance to right-wing extremism. Some of the most effective resistance so far comes from the churches, and I was reminded of an ecumenical inner-city ministry I was part of in the 1970s. See? It all fits together after all. Well, kinda.

Anyway, that’s when the spirit spoke to me. As the spirit is sometimes wont to do, it changed the subject.

We’d talked in the small-group discussion about the nature of sin and repentance. Who’s the sinner here? The prodigal? The elder brother? Both? Then, when I got home, I remembered a song that social justice activist John McCutcheon played 40 years ago at Jubilee Community Arts events back in Knoxville. It has quite a different take on the Prodigal Son, and it got me rethinking again.

Titled “I Shall Arise,” it’s based on the text (in the King James bible) when the son resolves, “I shall arise and go unto my father / And say unto him, Father I have sinned against heaven and before thee.” And along with songs like Si Kahn’s “Government on Horseback” (sample lyrics: “Blow out the lamp beside the golden door, / We don’t need cheap foreign labor anymore”), I remember it as a combination 1980s protest song and a southern Appalachian countercultural anthem.

You can hear a 1986 recording of John McCutcheon’s “I Shall Arise” on YouTube by clicking HERE. Amateur vocal recordings are HERE and HERE, and the Rise Up Singing website has info HERE; I have a copy of the songbook around here somewhere in my remarkably cluttered home office, but those are among the saddest words of tongue and pen, and I can’t find it to look up the word.

“I Shall Arise” certainly sounds like an anthem. McCutcheon’s arrangement is instrumental, with his melody line on hammer dulcimer and synthesizer backed by the late Fryda Epstein and members of the string band Trapezoid on fiddle, cello, upright bass and more dulcimers.The song is a round, and it builds to a climax that has always struck me as almost triumphal. Just hearing it makes me want to go out and join an informational picket line.

If nothing else, “I Shall Arise” gives me a new take on the Prodigal Son. On life in general. Something like this: So you repent? OK, good for you. It never hurts to think things over. Now what are you going to do with this new life of yours?

Dwelling in the Word: ‘Let me tell you a (bible) story’

My latest encoiunter with the Prodigal Son began with small-group discussions on the pericopes, or assigned readings for Sunday services, we hold after church at Peace Lutheran. They’re part of Dwelling in the Word, a program of the ELCA’s Central/Southern Illinois Synod that encourages participants to sit “together with a text for a period so that the reflections, wonderings, and promptings of God’s Word form and shape our faith and living.” It is very specifically not about “getting to particular results but rather allowing ourselves to be present with God’s living Word.” The format is built around three standard questions:

- What do I notice? What captures my attention?

- What questions do I have? What do I wonder?

- Where might God’s Spirit be nudging us?

As we talked about the story, I think we all realized how multilayered and open to interpretation it is, and we learned from each other. The questions are designed to elicit that, and I know they do wuith me. So what follows is my reconstruction of Luke’s bible story as I came to understand it. As always, I like to begin with a Jesuit exercise that puts me in the scene of a gospel story. Any gospel story. So let’s picture, or compose, the scene as I imagine it.

Jesus of Nazareth, as Luke tells us in Chapter 15, is on his way to Jerusalem, drawing big crowds as he passes through the villages of Samaria (the West Bank of the Jordan around today’s Nablus and Ramallah). In addition to ordinary riffraff (the am ha’aretz), he attracts the attention of scribes and Pharisees — the religious establishment of the day — and he’s asked repeatedly why a rabbi and a teacher like him spends so much time, with outcasts, Roman collaborators and sinners?

Welp, he says, it’s complicated.

Jesus tries homey analogies from Galilee. Sinners are like fig trees, he says. Any farmer knows you have to tend them for several years before they bear fruit. But these scribes and Pharisees don’t know anything about fig trees. They must live in town. Jesus tries again. It’s like a shepherd who looks for a lost sheep. And again. A widow loses a coin and drops everything till she finds it. Same reaction.

But, but, but — they ask, what about hookers? And guys who hang out with hookers? Aren’t they sinners?

“OK,” says Jesus, exasperated by now. “How’s about I just tell you a story?”

Or maybe it came down differently: The crowd’s friendly. Farmers down this way know fig trees, too, and they like Jesus’ little stories of the shepherd and the widow. Even the Pharisees say they hadn’t thought of things that way before.

As the gathering is breaking up, a guy comes up to Jesus, and he’s got a question. (I know, I know, Luke doesn’t say anything about him. But I like to imagine myself in the gospel stories, and the guy’s standing in for me) He and his family have a farm nearby, but his deadbeat little brother hit their father up for half the inheritance and blew it at the whorehouses around King Herod’s garrison in Sebastia (modern Nablus). Now he’s back, freeloading again, and the old man’s letting him get away with it. How can I out a stop to this before he gives away the rest of the farm?

Jesus thinks a minute, decides to answer the question with a question.

One thing parables are good for is “metaphorical language which allows people to more easily discuss difficult or complex idea” (I’m cribbing from WIkipedia). Jesus has a pretty good idea who’s the sinner here and who’s more sinned against than sinning. After all, it’s his parable! But he doesn’t want to come out and say it. Better to let the guy sit with it, figure it out for himself.

“Here,” says Jesus. “Let me tell you a story.”

So he tells the guy (my first-century stand-in) a parable about two brothers squabbling over a farm. One cashes out his share of the operation and blows the money, but he repents and comes home. The other stays on the farm, but he’s consumed with resentment. The question Jesus wants the guy (my stand-in) to answer remains unspoken. Who are the sinners here? Which brother am I? Younger? Elder? Both? Reading it 20 centuries later, I have the same question.

That’s the way it goes with stories, they leave you thinking. Especially Jesus’ stories. It’s like John Dominic Crossan of the historical Jesus seminar once said, “[…] if an audience filed past him afterward saying, ‘Lovely parable, this morning, Rabbi,’ Jesus would have failed utterly.” Crossan also has a nice “introductory definition” of a parable — “a story that never happened but always does—or at least should.” (Both quotes are from his book The Power of Parable: How Fiction by Jesus Became Fiction about Jesus, which I’ve got around here — somewhere — but I’m cribbing from the Goodreads website.) You can pack all kinds of meaning into a story, and different people can draw different meanings from it.

So where is the spirit nudging me?

So we had a good (do I dare say spirited?) discussion of the Prodigal Son after church Sunday morning. But with Dwelling the Word, it doesn’t stop there. When they’re working right, those questions lead me to more questions. Especially that last one. “Nudging” is the right word for it, too. The Holy Spirit doesn’t speak to me in signs, visions and wonders — it drops hints, whispers in my ear or gives me sneaking hunches I’d better take another look at something. That’s what happens when we repent (the New Testament Greek word, metanoia, comes from roots meaning change and thinking). And that’s what the Prodigal Son is about. Repentance and reconciliation.

All of which led me this time — or “nudged” me — in quite an unexpected direction. I’ve been thinking a lot recently about how mainline Christians can best respond when the duly-elected Trump regime cozies up to fascist dictators overseas and, as Michelle Boorstein, longtime religion reporter for the Washingon Post, puts it, “attacks […] religious groups, including Catholics and Lutherans.” Says Boorstein:

These attacks may signal a new political approach toward religion, some experts say, one comfortable belittling faith groups — despite President Donald Trump’s self-described brand as a champion of Christians. More broadly, it has aligned some Republicans against religious groups that in some cases propelled their rise to power, Trump’s included.

Boorstein’s comment was appropriately hedged and sourced to “some experts” (not all) but it was pretty jarring to see my Lutherans accused — without evidence and without later retraction — of “illegal payments” and “money laundering.” She added that-Gen, Mike Flynn, a Trump ally. “put quote marks around the word ‘Lutheran’ — one of America’s largest Protestant groups — in the post.”

(He put us in scare quotes? How’s that for a nasty, gratuitous little dig at somebody else’s religion? It strikes me as a snide way of telegraphing to the world your faith doesn’t matter, isn’t a real faith. Just like ICE agents detaining Muslims on their way to a public Iftar meal during the Ramadan fast. Who’s next? Will ICE come swooping down on a Lenten soup supper? A lutefisk dinner? When they come after the illegal Lutheran money launderers, who will be left to speak for me?)

And that’s about when the Holy Spirit started whispering in my ear. Chill, brother. Let’s think it over. Or, to stretch the metaphor a little, planted an earworm. .

I first heard, John McCutcheon’s “I Shall Arise,” during a similarly dark time. Back in my hippie days, McCutcheon was affiliated for a while with something called the Epworth ecumenical ministry in a transitional neighborhood next to the University of Tennessee campus; he said he learned the song from a busker over in Asheville, NC, and I heard it around Epworth at festivals and street fairs during the 1970s. So the instrumental version is associated in my mind with benefit concerts the Brookside miners’ strike and other worthy causes. of the day.

My involvement with Epworth came a little later. President Reagan was newly elected. Funding was drying up for the arts and community action, and Epworth was transitioning from a church-based inner-city ministry to a 501c3 not-for-profit called Jubilee Community Arts and “dedicated to the preservation and advancement of traditional music and art forms of the Southern Appalachians.”

It was a dark time for me, too. I was stuck in a dead-end newspaper job, and the colleges and government agencies weren’t hiring. So I applied for a TA at Penn State — it seemed like my only ticket out of town. Shortly before I left Knoxville, I joined the JCA board to help draft the mission statement and public relations material. Somehow we survived — I should say they survived, because the hardest work came later — and JCA is still there, (with the same mission statement, no less), holding concerts in a first-class regional venue with the brilliant acoustics of a restored 19th-century church building.

So the other day when I got home from church snd the Dwelling in the Word prompt asked where the Holy Spirit might be nudging me, it isn’t like choirs of angels came down from heaven singing “I Shall Arise,” but it had the same effect. I found it on YouTube, not only John’s instrumental but a couple of vocals with words pretty much as I remember them from his story about the street musician in Asheville.

Which brings me back to the bible story.

In Trump’s America, we’re a long way from the first-century Roman empire. (Or are we? Do I hear a still, small voice whispering in my ear again?) Remembering what the outlook has been like for social justice in my lifetime, it turns out I may have more in common with the Prodigal Son than I thought I did.

There’s no way I can make him out to be some kind of social justice warrior. (The elder brother is no better, but at least he’s conscientious — I can imagine him as a reliable GOP precinct committeeman. Or a Roman collaborator.). But I can see myself as a first-century Palestinian Jew listening to Jesus preach along the roadside north of Jerusalem.

And I can’t help but identify with.the younger son, the prodigal (Don’t ask!) My drinking and carousing days, like his, are in the past. But I can imagine myself sitting there in a first-century pigsty wishing I could eat the pods he’s feeding the pigs and thinking something isn’t quite adding up here, maybe it’s time to think again. To repent?

I’d like to think my sins are different than the Prodigal Son’s, and I might tell different stories about them. But sin is sin. An empire is empire, no matter whether it’s in Palestine in 33 CE, Knoxville in 1982 or Springfield, Illinois in 2025. And a pigsty is still a pigsty, and we do whatever we can to put them behind us.

[Revised and uplinked, April 8, 2025]