For several years now, an internet meme has been a mantra of mine when the news gets unbearable. Or, maybe, a talisman. More likely some of both. It purports to be a quote from the Talmud, but actually it’s a paraphrase or mashup of passages from a prophet in the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament, and a Jewish sage who flourished in the years after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. I want to engage it more deeply, and I think the Christian discipline of lectio divina offers me a way.

The prophet was Micah, and the Talumdic sage was known as Rabbi Tarfon. The paraphrase is by Rami M. Shapiro, an American Reform rabbi whose spirituality is grounded in Judaism but “draws on everything from Zen Buddhism to Catholicism and recovery’s Twelve Steps,” as a writer for Tablet magazine puts it. If a passage from the Talmud seems like an odd choice for a Christian exercise like lectio, I think I can approach it in Shapiro’s ecumenical spirit without cultural appropriation.

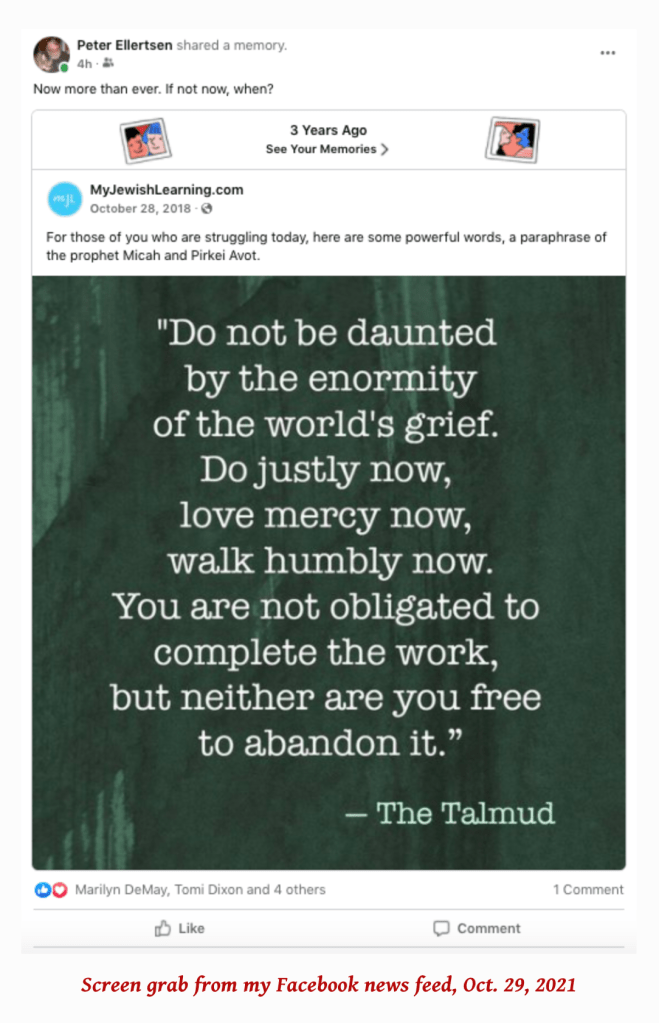

I first saw it shared in 2018 by the MyJewishLearning.com website, on Facebook, the day after 11 worshippers at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh were shot to death by a domestic terrorist who hated Jews and immigrants. “For those of you who are struggling today,” said the headnote, “here are some powerful words, a paraphrase of the prophet Micah and Pirkei Avot” (a collection of sayings sometimes known in English as the Ethics of the Fathers).

I was struggling that day — any mass shooting is upsetting, and this one triggered thoughts of the 2008 murders at Tennessee Valley Unitarian Universalist Church in Knoxville, where I went to services before I moved up north. The shooter hated liberals, Democrats and the media, along with minorities and others; I identify with all three, and I still had warm memories of TVUUC. So I took it more personally than your average mass shooting.

Anyway, I shared MyJewishLearning’s meme to my Facebook account. “Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief […]” That spoke to me. It continues to speak:

- Three years later, on Oct. 29, 2021, the meme showed up my Facebook memories. It still resonated, and I blogged about it HERE. Nothing immediately awful was going on at the moment. Just the everlasting steady drumbeat of mass murders, autocratic rumblings by former President Trump and speculation by respectable scholars that America is headed for civil war. As I researched the quote, I came across a Twitter thread by Jessica Price, a self-described “[g]ame tastemaker,” producer and writer, who traced it to Shapiro’s translation of the Ethics of the Fathers. “In addition to being a rabbi, teacher, and essayist,” said Price, “the author, Rami Shapiro, is also a poet, and sometimes it takes the principles of good poetry to make ancient texts accessible.”

- At the first of March 2022, shortly after Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, I was again daunted by the world’s grief, So I shared the meme to the blog, HERE, with thoughts about “thoughts and prayers,” action and the enormity of the world’s grief from James Martin, the Jesuit author, and Rachel Danziger, a lifestyle columnist for the Times of Israel. “There is blood on the ground in Kyiv,” said Danziger. “There are women birthing in metro stations in Kharkiv. There are elderly people hiding in their basements, children crying and explosions above their heads. We pray for God to extend His hand and help them, but it is OUR hands and legs and hearts that are required.”

- This fall, after the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza flared up, I quoted Rabbi Tarfon HERE, in a blast email to a parish book study group Debi and I moderate. We noted that the treatment of Palestinian people in the occupied territories reminded me of Jim Crow in America, which we had been studying; we wrote: “Let’s keep thinking – and talking — about what we can do as church. We are reminded of a quote – a paraphrase, really – from the Talmud: ‘Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. Do justly now, love mercy now, walk humbly, now. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it’.”

Now, at the end of a year that has seen more than its share of the world’s grief — and my own, as I went through chemotherapy, major surgery and, now, immunotherapy for stage 4 cancer — Rabbi Tarfon’s wisdom, and the prophet Micah’s, come back to mind. In his introduction to Wisdom of the Jewish Sages, Rabbi Shapiro suggests we’re all like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, and we find integrity and coherence only in relation to the other pieces, to each other:

This is what it means to be created in the image of God. The mission of the individual is to take his or her place in the puzzle by letting go of the illusion of fragmentation and bringing things into harmony with each other. This is what our Sages call Tikkun haOlam, the repair of the world. (viii-ix)

Tikkun haOlam, or Tikkun Olam, literally means “repairing of the world” in Hebrew. Wikipedia, my go-to source for all the world’s religions, notes that a common “modern understanding of this phrase is that we share a partnership with God, and are instructed to take the steps towards improving the state of the world and helping others.”

If ever the world needed fixing, now is the time.

Lectio Divina

As long as I’ve been inspired by Rabbi Tarfon’s (or Shapiro’s) wisdom, I’ve wanted to come to a deeper understanding of it. Lectio divina seems like an ideal technique for doing that. It’s an ancient form of prayer or meditation, ascribed to St. Benedict in the sixth century. It’s by no means limited to Benedictine monasteries, though, and I’ve found several Jesuit authors to be helpful in my own explorations. Becky Eldridge, a spiritual director of Baton Rouge, offers this overview on the Loyola Press website:

Lectio divina is a slow, rhythmic reading and praying of a Scripture passage. You pick a passage and read it. Notice what arises within you as you read it. Then you read it again, and then again, noticing what words and phrases grab your heart and noticing the feelings that arise. You respond to God about whatever is stirring within as you read and pray with the passage. Finally, you rest and let God respond and speak to you.

James Martin, SJ, adds another step. “Finally,” he says, “you act.” Often that action can simply be resting or contemplation, but I like Martin’s emphasis on action.

So let’s give it a try.

(I’ll follow a traditional four-step rubric from the Jesuit Institute of London in my headings below.)

Reading (lectio). As it usually appears on the internet (HERE, for example, HERE and HERE, in an array of websites ranging from a knitting blog to an interdenominational Christian church and a college chaplain), Shapiro’s paraphrase of the Talmud (and Micah) reads: Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. Do justly, now. Love mercy, now. Walk humbly, now. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it. The order has been changed around a little, but I’ll stick with the version we see on the internet.

That first line always hits me like a hammer blow.

The world’s grief can vary from day to day — a mass murder; war crimes and accusations of genocide in Ukraine, Israel and Palestine; and, always, the bitterly divisive polarization of our political life. But it is always with us. Always. Rabbi Tarfon flourished during the generation just after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, so he was acquainted with the enormity of world’s grief.

Tarfon was an interesting guy. He was wealthy, descended from Temple priests; he was lenient in his interpretation of Jewish law; and his modesty and generosity were legendary. Once in a time of famine, according to Wikipedia, “he took 300 wives so that they might, as wives of a priest, exercise the right of sharing in the tithes.” A story preserved in the Babylonian Talmud records:

Rabbi Tarfon and the Elders were once reclining in the upper story of Nithza’s house, in Lod, when this question was posed to them: Which is greater, study or action? Rabbi Tarfon answered, saying: Action is greater. Rabbi Akiva answered, saying: Study is greater. All the rest agreed with Akiva that study is greater than action because it leads to action.

But action is essential. “Paraphrasing Akiva, study is greater because it leads to action,” says Aaron Dorfman in a commentary for MyJewishLearning, “but only if it leads to action.”

That line from Rabbi Tarfon, do not be daunted by the world’s grief, occurs in a longer passage Shapiro adapted from Pirkei Avot (the Ethics of the Fathers); it follows a passage that counsels: “Discipline yourself to attention; / for the alternative is despair.” In Shapiro’s paraphrase, it’s followed by a snippet from Micah: Do justly, now. Love mercy, now. Walk humbly, now. The words are different, but I think the context is the same.

And as I read Shapiro’s interpretation, I get the message that the way to overcome the grief of the world, the alternative to despair, is to seek justice and mercy, and to do it humbly. The prophet Micah, for his part, was active around 700 BCE; like other prophets, he forecast the destruction of Judah for turning away from God’s commandments. Again, the context matters; Shapiro’s quoted passage follows right after the prophet says “the Lord has a case against his people, / and he will contend with Israel.” The Lord is not pleased with burnt offerings from the people of Israel, with “thousands of rams, / with ten thousands of rivers of oil. Instead, says Micah:

He has told you, O mortal, what is good,

and what does the Lord require of you

but to do justice and to love kindness

and to walk humbly with your God?

As I read it, Shapiro’s version is like a mashup of genres. It begins like a lament, one of those descriptions of suffering and anguish in the Psalms, but instead of crying to the Lord for deliverance, it turns to the kind of wise counsel found in the wisdom literature of the Hebrew Bible. And thus, according to Wikipedia, in Pirkei Avot or the Ethics of the Fathers. God watches over us, but it’s up to us to repair the world. Or try to.

The last line, in Shapiro’s version, also echoes the wisdom literature. To me it has a realistic, not-quite-cynical tone that’s more like Proverbs or Ecclesiastes than the hymns of praise to the Lord of Hosts in the Psalter. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it. Realistic? Yes. Suited to the present moment? Yes. Absolutely. To all moments throughout time? Probably.

Meditation (meditatio). “Reflect on what God might be saying to you through these words or images,” suggests the Jesuit Institute’s tip sheet. Well, the plain sense of the words is pretty clear. The world is a broken, awful, tragic mess, and it’s beyond my power to fix it. But that doesn’t mean I’m not obligated to try.

But there’s more to it. “Note your response,” adds the tip sheet, quoting from St. Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises, “in particular [where Ignatius says:] ‘I notice and dwell on those points where I felt greater consolation or desolation or had a greater experience in my spirit’.” Consolation and desolation are terms of art in Jesuit spirituality, part of what is called discernment of spirits; as I understand it, Ignatius believed that consolation comes from a “good spirit,” ultimately from God, and desolation from an “evil spirit.” Consolation, according to a “Jesuit 101” survey, is marked by faith, hope, charity and interior joy; desolation by agitation and despair.

There’s something else, too, at least as I experience it. I’ve been fighting cancer for a little more than a year now, and I’ve had more than my share of bad news to absorb. (That sounds like a spirit of desolation talking, by the way.) On the other hand, I can’t really say it’s been more than my share. I’m 81 years old, way past my allotted threescore years and ten. If I were a car, I’d be a high-miler, maybe a 1977 Chevy with rusted-out quarter panels. (Is that a spirit of consolation I hear? C’mon spirit! A little louder!) So I’m troubled not only by wars, rumors of wars and speculation about the horrors that await us in next year’s election cycle.

I have my own troubles. too. Cancer, obviously, at the top of the list. Plus all the other aches, pains and foibles of old age. But maybe some of the wisdom that’s reputed to go with it, too. Plus, I’m getting to know the folks at the infusion center and interventional radiology by name. There are compensations.

And that internet meme from Rabbi Tarfon gives me what I take to be some pretty good marching orders.

Do justly, now. Love mercy, now. Walk humbly, now. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it. You know what? It works. I feel better when I get outside my own drama and do something nice for somebody else. I understand there are scientific studies about this. Says Jeanne Lerche Davis of WebMD, citing Stephen G. Post, professor of bioethics at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, who has conducted several of them:

“All the great spiritual traditions and the field of positive psychology are emphatic on this point — that the best way to get rid of bitterness, anger, rage, jealousy is to do unto others in a positive way,” Post tells WebMD. “It’s as though you somehow have to cast out negative emotions that are clearly associated with stress — cast them out with the help of positive emotions.”

So it’s good science. I think WebMD and the “good spirit” of Ignatian discernment are saying the same thing, and it works for me.

Response (oratio). In a word, this is about prayer. “I speak to God my Lord,” advises the Jesuit Institute of London, again quoting Ignatius, “in the way one friend speaks to another — ‘telling my concerns and asking counsel about them’.”

Like one friend speaks to another? OK, here goes: Thanks, buddy. Thanks for internet memes, Rabbi Tarfon, the Jesuits, WebMD and all the places, likely and unlikely, where I find wisdom and consolation. I’ve tried some of the stuff you recommended, and it seems to work. Glory hallelujah, it works!

Back in the spring, I had some pretty serious complications from chemotherapy and surgery, and I was awfully sick for a while. But somewhere along the line, I got the idea that well, at least I can just be nice to people when I don’t feel like it, and maybe that’ll help me feel better.

I started small, trying to be cheerful and polite to hospital system receptionists even when they kept me on hold forever — it isn’t their fault, I told myself, the health case system is broken — thanking them and wishing them a nice day when I finally got through to someone. Often enough, you could almost hear them sparkle over the phone. ‘Oh, thank you! We don’t usually hear that.’ I don’t think I would want to be in their line of work — I don’t think a lot of the people they talk to in a day’s work are happy campers.

I could go on at some length, God, but I think you get the drift. It helped me get over the sour vibes I got from a medical specialist whom I won’t identify further …

So, it worked. I don’t know exactly what I was praying for back in the spring when things got so bad. Well, yes, no, I guess maybe I do. The 11th Step of Alcoholics Anonymous tells us to to pray “only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.” So that’s what I did. (Mostly.) And that’s what I got. (Mostly.) Just try to be nice to people. Or as Rabbi Shapiro might put it, try “bringing things [or people] into harmony with each other.” (In my small way.)

So, OK, my next question: What’s next?

Oh, OK, you’ll let me know in your own way at a time of your own choosing. Sure. Why not? That’s the way it usually works, isn’t it?

Contemplation (contemplatio). Most of the how-to guides on lectio divina I’ve read speak, as the Jesuit Institute does, of “a quiet and attentive resting in the presence of God.” Fr. Martin, however, puts a spin on it that I like. The fourth step, he calls Action. “What do I want to do,” he asks, “based on my prayer? Finally, you act. Prayer should move us to action, even if it simply makes us want to be more compassionate and faithful.”

We are not obligated to finish the work, Martin might have added. But neither are we permitted to abandon it.

Links and Citations

Alcoholic Anonymous, The Twelve Steps https://www.aa.org/the-twelve-steps.

Jeanne Lerche Davis, “The Science of Good Deeds,” WebMD https://www.webmd.com/balance/features/science-good-deeds.

“Do Not Be Daunted – Dec. 7, 2020,” Inward/Outward Together, Church of the Saviour, Washington, DC https://inwardoutward.org/do-not-be-daunted-dec-7-2020/.

Aaron Dorfman, “Learning and Doing,” My Jewish Learning, 70 Faces Media, New York https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/learning-amp-doing/.

Becky Eldredge, “Lectio Divina,” Loyola Press https://www.loyolapress.com/catholic-resources/prayer/personal-prayer-life/different-ways-to-pray/lectio-divina/.

Carolyn Fure-Slocum, “How are we to be?” Reflections from the Chaplains, Office of the Chaplain, Carleton College, Northfield, Minn. https://www.carleton.edu/chaplain/reflections/.

James Martin, “Read, Think, Pray, Act: ‘Lectio Divina’ in Four Easy Steps,” Word Among Us, Nov. 2007 [dead link, quoted on my blog at https://ordinaryzenlutheran.com/2019/07/24/lectio-divina/].

Micah 6:1-8 [NRSVUE], Bible Gateway.

Ian Peoples, SJ, “Jesuit 101: Consolation and Desolation,” The Jesuit Post, March 11, 2022 https://thejesuitpost.org/2022/03/jesuit-101-consolation-and-desolation/.

Wayne Robbins, “A Rabbi Seeking Wisdom Across Religious Lines,” Tablet, June 4, 2015 https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/community/articles/rabbi-rami-shapiro.

Rami M. Shapiro, Wisdom of the Jewish Sages: A Modern Reading of Pirke Avot (New York: Bell Tower, 1995), viii-ix, 40-41.

Amy Snell, “Do Good Now,” The Devious Knitter, April 26, 2022 https://deviousknitter.com/do-good-now/.

Wikipedia Benedict of Nursia, Knoxville Unitarian Universalist church shooting, lament, Lectio Divina, Micah (prophet), Mishnah, Pirkei Avot, Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, Psalms, Rami M. Shapiro, Talmud, Rabbi Tarfon, Tikkun Olam and wisdom literature.

[Uplinked Dec. 23, 2023]

Nice!

LikeLike