On the way back from visiting family in the Quad-Cities on Christmas Day, we tuned in to the public radio station from Champaign. As we zipped down Interstate 155 from Peoria to Lincoln and onto I-55 toward home, they aired a dramatic reading from Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. A 45-minute dramatic reading was the last thing on earth I would have chosen to listen to, but we were a captive audience — there aren’t that many choices on the radio Christmas night in downstate Illinois — and it got me to thinking.

Sometimes I think driving down the interstate late at night is the only time I have for extended contemplation. The only time I make time for it, at least.

Anyway, we listened to every word of Christmas Carol — Marley’s ghost; Ebenezer Scrooge’s visions of the spirits of Christmas past, present and future; and his final redemption as he cried out in a graveyard to the Spirit of Christmas Future, “I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach. …” (Note to reader: I’m cheating now, I just looked it up to refresh my memory). And forthwith, the Spirit “dwindled down into a bedpost” and “[b]est and happiest of all, the Time before him was his own, to make amends in.”

A nice Victorian happy ending, in other words. Dickens was one of the all-time great English writers, but he wasn’t above working a little schmaltz into the story when it helped him sell books.

Two things stood out as we listened on the car radio — Dickens was a far more subtle craftsman than I’ve given him credit for (and he was already my very favorite 19th-century English novelist), and he wasn’t above poking a little fun at himself … and, while he was at it, poking fun at the conventions of Victorian society and literature.

And the second thing really stood out — in spite of the whiffs of Dickensian irony — for all his Victorian schmaltz, damn it all, Dickens had a point there. Time is running out, and in spite of everything, there is still time to make amends. God bless us every one.

Somewhere around the 100-mile marker just north of Springfield, Dickens went off the air. And I started thinking about New Year’s resolutions. I don’t do them. When I’ve tried to, they’ve never lasted. So I figure I’m better off without the pretense of making them.

But the word picture of Ebenezer Scrooge arguing with the Spirit of Christmas Future in a graveyard stayed with me.

“Men’s courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead,” Scrooge implored the Spirit. “But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change. Say it is thus with what you show me!”

With the year’s end coming up, barreling up on me, I’ve been thinking lately about the historical research I used to do on music history, Swedish immigration and the old Swedish-American Augustana Evangelical Lutheran Synod. Up until two or three years ago, I was publishing articles — including a real spellbinder titled “‘How Newness Enters the World’: Cultural Creolization in Swedish-American Hymnals Published at Augustana College, 1901-1925” — and presenting papers at regional historical society conferences.

Now it seems like I spend my time on the internet searching for articles on current events — starting my day with thoughts of “OMG, what’s Trump done now?” — and arguing with strangers on Facebook about immigration policy or why “the Left” hates, or doesn’t hate, America — or Trump — or whatever the outrage de jour might be. I haven’t presented a paper since 2017, and I’ve been stuck on the same article for two and a half years.

(Not all or this, or even most of it, is Trump’s fault, of course. I joined Facebook about the same time he started his presidential run in 2015, and I’m a lifelong political junkie. Plus I’m easily distracted. So I was always going to spend too much time on the journalistic ephemera of the day. Even that article I can’t get to jell has benefited, I think, from long periods when I was rethinking its premises. A little writer’s block isn’t always a bad thing.)

But barreling down I-55 on Christmas night, my thoughts keep returning to Ebenezer Scrooge arguing with the Spirit of Christmas Future in a “graveyard overrun by grass and weeds, the growth of vegetation’s death, not life; choked up with too much burying.” In Dickens’ story, Scrooge wakes up the next morning and immediately — immediately — opens the window and cries out, ““I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future! … The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. Oh Jacob Marley! Heaven, and the Christmas Time be praised for this! I say it on my knees, old Jacob; on my knees!”

We’re crossing the Sangamon County line now — 15 miles to go — and there is still time. Like Scrooge, I’m all “fluttered and so glowing with … good intentions.” God bless us every one. And that article I’ve been working on is still waiting for me at home. Waiting in three or four different folders on my hard drive, as a matter of fact, reflecting three or four different false starts over the past 18 months or more.

I’ve already done the basic historical research. It involves an obscure point of ecclesiastical polity, or church governance, but it can have larger implications — at least it might if I think them through carefully enough and bring them out clearly enough.

When the first Swedish and Norwegian pastors came to America in the 1850s, they encountered a different attitude toward church membership than that of the established state churches in the old country (Sweden and Norway were ruled by a joint monarchy at the time). From the Puritans onward, churches in America tended to be voluntary associations of believers — of the elect — but if you were a subject of King Karl Johan, you were a member of the Lutheran folk church, or people’s church, and that was that. So when they came to a new land where church and state were separate, pastors and parishioners alike had to adapt.

Swedish Lutherans also had to adapt to the prevailing Reformed, or Calvinist, attitudes and practices regarding church membership. The theology here gets a little obscure (and it’s an open question how typical of Calvinism it was), but its day-to-day implications were pretty stark. In an era of fire-and-brimstone sermons, altar calls and emotional conversions, applicants for church membership often were required to document a conversion experience — i.e. a specific moment when they specifically decided to accept Jesus Christ as their personal Lord and savior, when they were “saved” in today’s parlance.

This created understandable problems for Lutherans, who typically were accepted into the church when they baptized as infants — and consequently had no recollection of any such event.

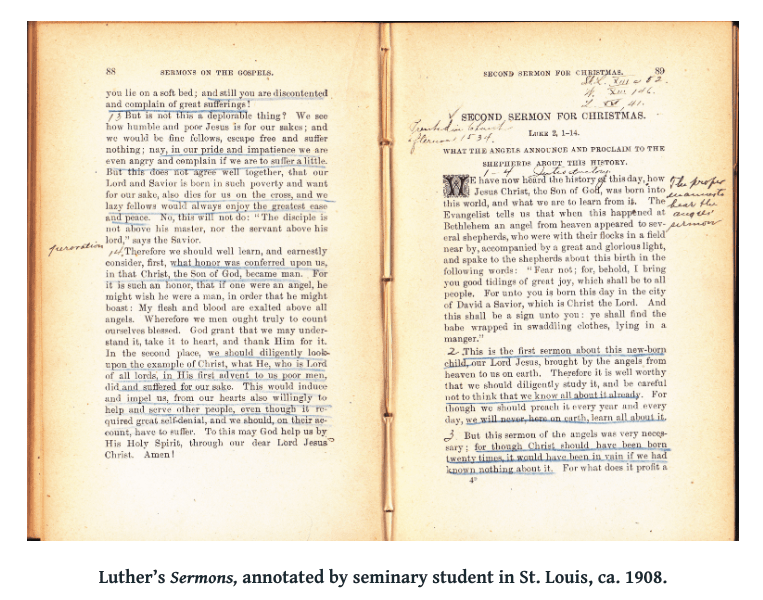

For example Luther’s sermons, or postils, which were commonly read aloud in immigrant congregations in the absence of an ordained pastor, were strongly at variance with the prevailing American orthodoxy of predestination, conversion and election. In a passage in a Christmas sermon he delivered in 1534 that’s especially clear in its implications, Luther said by Christ’s incarnation, sinners were “received into citizenship of the dear angels” who proclaimed the good news to the shepherds in Bethlehem:

They, the dear angels, … do not say: I do not like this sinner, this stinking corpse, these condemned, unclean whoremongers and profligates. No, they do not say thus; but they rejoice heartily that they now have such sinners for friends and associates, and praise God for this, that we, being delivered from sin, come with them into one house and under one Lord.

This is about as far as you can get from the fire-and-brimstone, sinners-in-the-hands-of-an-angry-God theology of 19th-century American camp meetings (even though I think it’s fair to say, especially with 150 years’ hindsight, many 21st-century Calvinists and Lutherans have ended up in pretty much the same place. Love God, love your neighbor.) In his 1534 Christmas sermon, Luther said:

How much more is it not meet [appropriate] that we also should thank and praise God therefore, and love and help one another, even as the Son of God did us, who became our flesh and nearest Friend. But whoever will not regard this, and will not thus love and serve his neighbor, for Him, as said above, there is no help.

Love God, love your neighbor. There’s more to it, of course. A lot more. But without getting lost in the thickets of 19th-century theological controversy, suffice it to say there’s plenty of grist there for a historical article. And it has resonance today.

For one thing, the way we think about the separation of church and state is still a matter of controversy. And the reaction of Swedish pastors in the 1850s, who were accustomed to what we now would call a folk, or national, church, might have lessons for us. Also of interest is the process of blending old-world and American customs — the technical word for this process is creolization, the concept I explored in that article I wrote on Swedish-American hymnals.

Especially at a time when white evangelical Protestants seek to impose their values on on a diverse, secular nation and America — at least the current American government — has turned its back on immigrants and its heritage as an immigrant society, I believe these things have resonance. A historical article or two might be a worthwhile addition to the debate.

All of that comes later, however.

For now, it’s a matter of sitting down, getting off Facebook for a minute or two, outlining, drafting, seeing what happens when I actually start putting words on paper (OK, OK, pixels up on a screen). I’m still not going to call it a New Year’s resolution — I know what happens when I do that (or what doesn’t happen) — but when I got home Christmas night, I found an old post on my research blog, from the spring of 2018, on Luther’s Christmas sermon and shared it to Ordinary Time. That’s a start.

And then we can see what happens next.

In the meantime, I invite any readers I have at this point to nag me. Hey, Pete, how ya doing with that article on Swedish immigrants? Maybe, just maybe it’ll help keep me from arguing with Ebenezer Scrooge and the Spirit of Christmas Future in some desolate graveyard a year from now.

So you’ve given me permission to nag … watch what you ask for! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, dear. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

😀

LikeLike